When did we come to Britain? You must be mistaken, Britain came to us

Adam Elliott-Cooper discusses how Britain's role as a major imperial power not only brought about mass migration, but has united an otherwise extremely heterogeneous Black population in struggle through their common experience of colonial violence. The 'diversity in unity' of such experience, and the memory od past struggles, are essential resources for the ongoing fight to tear down the structures of racial oppression which persist in Britain today.

Recently, we have seen anti-racist resistance organised against racist border controls in solidarity with refugees and migrants. Amongst other actions, Black Dissidents, Sisters Uncut, London Latinxs and other activists blocked the Eurostar departures in St Pancras Station on Friday 16th October.

Black Britain, possibly more than any African diasporic population on the planet, is incredibly diverse. It consists of people that hail from a range of Caribbean islands, from cultural powerhouses like Jamaica, to tiny protectorates, like Monserrat. Increasingly, Black people in Britain have migrated from the African continent, from former British colonies like Nigeria and Kenya, but also places like Congo or Somalia - not to mention the myriad of subnational groups, languages, cultures and histories which reside within these countries.

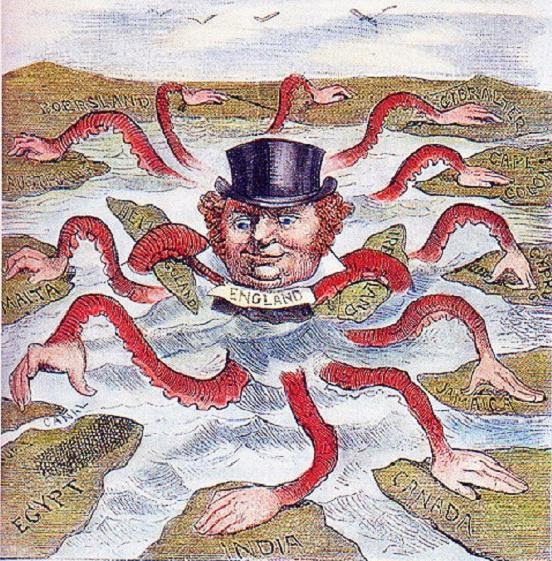

One of the things that unite these people is the racial violence of the British Empire. Today, we've seen that violence transposed to the centre of Empire, through policing, the prison system, poor housing/gentrification and educational exclusion. The heterogeneity of Britain’s Black population appears extraordinary, until we reflect upon Britain’s position as the imperial centre of the world for so many centuries, and the far-reaching influence it had upon its colonies and the people it ruled.

Yet, despite having one of the most expansive Empires in human history, shaping the racial borders which mark today’s globalised world, Britain is reluctant to discuss ‘race’. Even much of the British radical tradition feels far more comfortable discussing ‘class’, implying that ‘race’ happens somewhere else - Johannesburg, Mississippi, or in the West Indies, perhaps. But being the centre of Empire for so many centuries, made Britain, in many ways, race’s administrative capital. Claiming victory in European competitive colonisation in the 19th Century, amassing the lion’s share of the transatlantic slave trade, and dominating the carving up of Africa, Britain’s East India Company and other colonial ventures were also supported by its philosophers. For instance, John Locke – often hailed as the quintessential theorist of ‘liberty’ – not only sought to justify the enslavement of Africans through a defense of property rights, but materially invested in slave-trading Royal Africa Company. Similarly, continental Enlightenment thinkers like Kant argued fiercely for the necessity of violence towards the ‘lesser races’, while the acclaimed Francis Galton coined the term ‘eugenics’, bringing ‘race’ into the modern, empirically-based, ‘rational’ realm of scientific thought. Through such administrative, institutional and ideological means, Britain governed race at arms length, with direct physical violence exported to its metropolitan outposts in the colonised world.

It is therefore unsurprising that Britain was the location of the first five Pan-African Congresses, serving as the administrative centre of anti-colonial resistance. Africans from both the continent and the diaspora met to plan self-determination for their people. Activists and Intellectuals like DEB DuBois, Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba and Marcus Garvey took differing routes to liberation, yet all understood the centrality of Britain as the heart of colonial power, and how this centralisation unified them all. As for centuries, the resources and labour of the colonised world flowed towards Britain, predictably, the people eventually followed. Some were invited to rebuild the country after World War 2. Those with the status of citizens of the commonwealth were able to move freely, while others navigated bureaucratic barriers and physical borders to make it to the mother country. Despite the variety of channels these colonial subjects followed, their reception was rarely dissimilar: an abrupt, and undeniable racism. These, very different, societies of disparate people eventually found themselves side-by-side, united by their blackness. Unlike their distant cousins in the United States, Black people in Britain didn’t have a shared history of oppression and struggle. Though they were struggling against the same imperial powers, the Mau Mau of Kenya, the Pan-Africans in Ghana, the trade unions of Jamaica or Trinidad, were for the most part separated by land, sea, language and culture.

When we take this into consideration, it’s remarkable that Black people in Britain have been able to establish and sustain anything resembling a cohesive anti-racist struggle at all. Uniting all colonised people under the term ‘Black’ in the 1950s was one such approach, and the creation of the label ‘Black British’, as apposed to Nigerian-British, or Jamaican-British, is another. From this emerged a Black Power movement which was in constant conversation with Britain’s colonies and former colonies. Many of its most influential organisers had been born under British colonial rule, leading the charge against the far-right, as well as social issues relating to housing, education and healthcare. Squatters movements helped black families find housing, while the black supplementary schools, pioneered by Gus John, challenged the racism in mainstream education. Mass action came to a head when confronting the violence of the state - with policing seeing revolts across Britain, such as Notting Hill in 1976, then Bristol, Nottingham, Brixton, Toxteth and other parts of England in 1981. These spontaneous rebellions were often accompanied by more organised resistance, which saw campaigns against racial violence grab national headlines and mobilisations like the 1981 Black People’s Day of Action, which galvanised an estimated 15,000 people.

But despite such a rich narrative of Black mobilisation on British soil, people with such distinct histories have often struggled to present a straight-forward narrative. Unfortunately, there is often a focus on pre-ordained Black historical epochs: the US civil rights movement, or the fall of apartheid (or as is more often the case, an excerpt from a speech by King, or Mandela). We can all relate to people wanting to stand up to racism, and are touched by the achievements they made. But at the same time, neither of these stories are really ours, and what often results from trying to relate to everyone, is a history that doesn’t really relate to any of us. Our current state leaves us with students who know about the Montgomery Bus Boycott, but may be shocked to hear that the British hanged 312 enslaved Jamaicans and put their heads on sticks in 1831 for rising up against their masters. Or the hundreds who were hanged in Jamaica’s Morant Bay Rebellion, for struggling against how Britain imposed colonial laws on its workers. Many students have heard of the ANC, but know little about the Convention People’s Party, the anti-colonial organisation that led Ghana to become the first African nation to free itself from British rule. Britain’s African diaspora has its own civil rights and anti-apartheid struggles - the overthrow of colonialism is, in many ways, a struggle for civil rights. Indeed, the battle for a passport to Britain and inclusion in the sharing of the resources it holds was, and still is, our movement against apartheid.

Today, state violence is the issue most immediate to Britain’s black communities. Deaths at the hands of the state, including immigration detention centres, prisons, mental health institutions and the police, still dominates Britain’s anti-racist narrative. While organisations like The Monitoring Group assist with legal cases for those who have suffered racial violence, others, like the London Campaign Against Police and State Violence offer training on Stop and Search or complaints, while supporting popular protest and civil disobedience. The movement for Black Lives in the US has regalvanised Black British protest, with solidarity actions organized by groups such as London Black Revs in Britain shutting down major commercial districts, like London’s Bond Street and Westfield in Shepherd’s Bush. This was an opportunity to not only build on emerging trans-Atlantic movements, but give the families of those killed at the hands of the British state a chance to develop a newer platform, reaching out to those angered by the news of racial violence US, with equivalent cases here in Britain gaining far less mainstream media coverage. Those representing deaths in custody campaigns, such as Justice for Sean Rigg, toured the US, cementing links with the campaigns across the Atlantic, and building on the growing interest in police violence. In many ways, the spirit of anti-colonial rebellion is still very much alive in the more radical sections of Black British political life, yet making these links in educational institutions and community spaces in the month of October continues to be a challenge.

A cynic might argue that the focus on places like South Africa and the United States plays conveniently into the hands of the British state, diverting our gaze from its own injustices. But such complexities are not just a barrier - they’re an opportunity. Unlike the United States, no one group within Britain’s Black population owns the narrative of Black people. In considering this, a formation of Black history in Britain can serve to not only tell a single story or viewpoint, but multiple stories and ideas. Due to these complexities, Black Britain, more than our distant cousins in the United States, needs Black history to be more than just a month. Drawing the links between our geographically disparate, yet intrinsically connected histories requires constant reflection. Pushing past the invisibility of racial injustice on British soil, which the Empire has hidden away in its colonies, means resistance, in action and in thought, must be a continual process if we are to understand how one of history’s biggest Empires can so easily negate the legacies of its power.

Adam Elliott-Cooper is a DPhil student in geography at the University of Oxford. His research focuses on how black communities in Britain are organising to address issues relating to policing.

For information about this year's Black History Month, click here.

Read more about #BlackLiberation on the Verso blog.

For further information about activist groups struggling against white supremacy, institutional racism and other forms of oppression suffered disproportionately by people of colour in the UK:

Defend the Right to Protest: Defend the Right to Protest was launched in response to violent police tactics and arrests at the student protests of November and December 2010, with the support of activists, MPs, trade unionists, student groups and others. DRtP campaigns against police brutality, kettling and the use of violence against those who have a right to protest. They campaign to defend all those protestors who have been arrested, bailed or charged and are fighting to clear their names.

London Campaign Against Police Violence: a group formed of south London communities fighting against police brutality and legal violence. ‘Our aim is to support victims of police assault and to link them in a London-wide campaign. We will be monitoring police harassment of our communities and people of colour in particular.’

The Monitoring Group: established in Southall (west London), in the early 1980s, by community campaigners and lawyers who wished to challenge the growth of racism in the locality. They are now a leading anti-racist charity that promotes civil rights.

The Sean Rigg Justice and Change Campaign: founded by the family of Sean Rigg, a Black man who died in the custody of Brixton Police in 2008. The campaign seeks to uncover the true circumstances of his death, as well as struggling for broader change.

United Family and Friends Campaign (UFFC): a coalition of those affected by deaths in police, prison and psychiatric custody which supports others in similar situations. Established in 1997 initially as a network of Black families, over recent years the group has expanded and now includes the families and friends of people from varied ethnicities who have also died in custody. They hold an annual demonstration, with this year’s scheduled for 31st October.

Black Dissidents: a UK-based group of militant black and brown activists, fighting for liberation by any means necessary. On Friday 16th October, 2015, together with Sisters Uncut and the London Latinxs, Black Dissidents organised protests against racist border controls and the resulting deaths of refugees, blocking the Eurotar departures in St Pancras Station and engaging in several other forms of direct action. Reports here and here.

Sisters Uncut: Feminist group taking direct action for domestic violence services. ‘We stand united with all self-defining women who live under the threat of domestic violence, and those who experience violence in their daily lives. We stand against the life-threatening cuts to domestic violence services. We stand against austerity.’

The London Lantinxs: ‘We aim to be a support system that fights for the rights of Latin Americans and of migrants in general, through organising, planning, improving representation, raising awareness, campaigning, workshops, and direct action.’