March

28

March

28

A Post-Kemalist Election:

The Republican People’s Party Approaches Its First Election Under New Leadership in Over a Decade

The 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections were a blow to the Turkey’s opposition. Since the 2019 municipal elections, there had been a growing sense that a broad alliance, held together by antipathy to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan might be sufficient for victory. Under the leadership of Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the Republican People’s Party (CHP) seemed to be successfully appealing to conservative, religious, and Turkish nationalist voters. At the same time, it was securing the tacit support of many Kurdish voters and retaining its secular, center-left base. The potential of this strategy was demonstrated in victories in both the Istanbul and Ankara metropolitan municipality races, where the CHP ran successful candidates with only limited connection to the party.[1] The strategy maintained the CHP’s position as the “main” opposition party but made it difficult to know what the party actually stood for.

When Kılıçdaroğlu maneuvered himself into the opposition’s presidential nomination in 2023 but failed to achieve either a plurality of the presidential vote in the first round or a majority in the second, the opposition was left without a clear path going forward. After a great deal of intra-CHP intrigue, Kılıçdaroğlu was forced out. The question remains, however, whether the strategy was flawed, or just the candidate.

The upcoming municipal elections, therefore, should be understood in two ways. The first—which we will come to—is as local contests with their own particular dynamics. The second is as a referendum on whether Kılıçdaroğlu-ism can persist without Kılıçdaroğlu.

Bidding Adieu to Kılıçdaroğlu?

Few opposition leaders would frame the contests this way. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu himself is thoroughly discredited. In a matter of weeks he went from receiving complimentary profiles to being called on to resign, depicted as a man whose “political greed” led him to sideline more electable presidential aspirants, giving away places on his party’s electoral list to former-Justice and Development Party (AKP) members in return for their support.[2] Nor are these criticisms merely ex-post facto recriminations. In the weeks between the first and second round of the presidential elections, it was apparent that Kılıçdaroğlu and his organization had no Plan B should they find themselves running behind Erdoğan in the polls. This period of was marked by a few days of uncertainty, followed by a strident appeal to nativist sentiment that included promises to send Syrian refugees back to Syria.[3] In the months after the election, Kılıçdaroğlu rebuffed calls to step down until he was forced out at the party convention.[4]

The new leader of the CHP, Özgür Özel, whatever his strengths, lacks the stature of past party leaders.[5] He is a stand-in for Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu. Yet Imamoğlu himself is a recent entrant to high-level CHP politics.[6] He secured a nomination in 2019 as part of Kılıçdaroğlu’s strategy to nominate candidates with appeal to conservative voters.[7] This strategy proved successful in Istanbul and Ankara, but it creates difficulties: Imamoğlu (like Ankara mayor Mansur Yavaş) is more popular than the CHP itself, but he also lacks solid support within the party. Kılıçdaroğlu had a decade to consolidate his influence; İmamoğlu has had around five months. Should he lose his mayoral race in Istanbul, it will be extremely difficult for him to retain a predominant role in the party.

Under Kılıçdaroğlu, the CHP nominated candidates like İmamoğlu who could secure support from rival political factions within Turkey’s fissiparous opposition movement. Following Kılıçdaroğlu’s defeat, these alliances have come apart. Both the far-right, Turkish nationalist Good Party (İYİ) and the left-wing/Kurdish movement represented by the Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM) have decided to run their own candidates in competitive mayoral races like Istanbul.[8] [9] The CHP too is riven by divides.[10] Some Kılıçdaroğlu allies have been replaced, causing resentment, while others—as in the example of Hatay, discussed below—have been renominated despite being controversial political figures.[11]

Given how well the opposition did in the 2019 municipal elections, the upcoming 2024 elections are likely to be a setback, and recriminations are likely to follow. But the question is the scale of the loses. Kılıçdaroğlu spent a decade attempting to make the CHP broadly acceptable to all opponents of the AKP. Can the party remain competitive in his absence?

Post-Peak Performances

In assessing Turkey’s municipal elections, it is important to appreciate that the AKP is the only truly “national” party in the sense that it is competitive in every province. There are only five provinces in which the AKP is not among the largest two parties in the local assembly (il genel meclis).[12] Other parties, like the far-right Nationalist Action Party (MHP) or the center-left CHP, are competitive in particular regions or provinces but lack national scope. In a conservative province like Tokat, where the CHP candidates won around 20% of the vote province-wide vote in 2019, the competition is actually between the AKP and the MHP; similarly, in a province like Batman with many Kurdish voters, the CHP wins around 3% and the real competition is between the AKP and DEM (still referred to as “HDP” in 2019).

Yet, given the dramatic variation in municipal populations, it is important to keep victories in perspective. In 2019, for example, the MHP won 11 major mayoral elections, but these were in lightly-populated regions of the country and accounted for only about 3% of Turkey’s population.[13] The political movement represented by the HDP, by contrast, won “only” eight major elections (three less than it had won in 2014), but these eight victories allowed the party to govern around 5.4% of the population.[14] This disparity is most striking in the comparison between CHP and AKP. In 2019, the CHP won 21 major races—about half the number won by the AKP—but these metropolitan municipalities (büyükşehir belediye) and central provincial cities (il merkez), in combination, contained some 45% of Turkey’s population.[15] These victories emboldened the opposition in advance of the 2023 elections. Little such enthusiasm remains today.

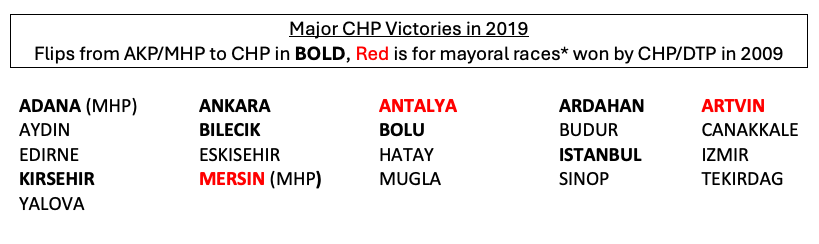

The scale of the CHP’s 2019[16] victory will be difficult to repeat in 2024. Compare those 2019 victories with the current situation:

- In Adana, the CHP won 53.6% of the vote in 2019. This was the largest province in which the AKP deferred to its coalition partner, the MHP, whose candidate, Hüseyin Sözlü, was the incumbent, having narrowly defeated the AKP’s candidate in 2014. In that election, Sözlü had benefitted from party splits. He had received the backing of Adana’s long-serving mayor Aytaç Durak, who was furious with the AKP for removing him from office as part of a corruption investigation in 2010. After he was acquitted and tested the waters for another run, Durak opted to support Sözlü in 2014.[17] In that election, the combined “conservative” vote for AKP-MHP was around 65%. The center/left vote was split between the CHP and DTP. In 2019, however, the CHP candidate, Zeydan Karalar, was able to benefit from party splits within the MHP—many of its members had left to form the İYİ and then backed him. Karalar was further helped by the HDP’s decision not to run a candidate. Thus, In 2019, the “conservative” candidate (Sözlü) recieved 42.8%, about 1% less than the AKP-MHP’s combined share of the provincial assembly. In 2024, both DEM and İYİ are running candidates; the CHP is running Karalar again; and the AKP-MHP are jointly backing Fatih Mehmet Kocaispir, the AKP mayor of Yüreğir, the largest AKP-run municipality in the province. If Karalar and the CHP hold on, it will be a significant victory for the CHP.

- In Burdur and Bolu, the CHP won the 2019 central municipality elections with 53.1% and 52.7%, respectively, but these victories depended on no competition from İYİ (the HDP ran candidates but the party receives negligible support in these provinces). In both provinces the CHP won far smaller shares of the provincial assembly (22.4% and 29.4%, compared with the AKP’s 42.6% and 45.3%). Given that İYİ is running candidates in both races in 2024, it is possible that the CHP could lose both Burdur and Bolu. (Though, in Bolu, the MHP is competing as well, which may keep the CHP competitive against the AKP.)

- The CHP won the central municipality election in Kırşehir with 44.8% of the vote, but this was a rare instance of the AKP and MHP both running candidates in a province where the CHP was competitive (and unchallenged by the İYİ or HDP). The conservative vote split 38.7%-to-15.6% and created an opening for the CHP. In 2024, all parties will be running candidates, which will likely benefit the AKP.

- In Aydın in 2019, the CHP won by a comfortable 10-point margin over the AKP (54% to 43.7%), but the division of the provincial assembly suggests this difference depended in part on the support of İYİ, and İYİ will be running a candidate in 2024. The same dynamic occurred in Antalya as well, with a similarly tight race likely. In Artvin, an 8-point difference in the central municipality mayoral race (51% to 43.2%) is nearly reversed at the level of the provincial assembly. As in Aydın and Antalya, the İYİ candidate will likely hurt the CHP’s chances in Artvin. (In Ardahan, the situation is repeated with DEM playing the same decisive role.)

- In Muğla, the CHP won in 2019 with only 36.2%. The 28.3% won by the AKP was nearly matched by the mayor of Fethiye, Behçet Saatcı, who ran as an independent won 26.2%. In 2024, Saatcı is running as a candidate for İYİ. Unless his connection with the party gains him votes, another CHP victory seems likely. In Mersin, the CHP won more narrowly, winning 45.1% against the MHP’s 40.1%. While İYİ, AKP, and HDP did not contest the mayoral race, a sizeable portion of the vote went to the conservative Democrat Party (12%). In 2024, the AKP has again deferred to the MHP candidate. DEM is not contesting the race, but the Democrat Party and İYİ are running candidates, which is likely to hurt the CHP’s chances in this tight race. This dynamic is repeated in Edirne, where the CHP mayoral candidate for the central municipality in 2019 won 44.9% to the AKP candidate’s 40.1%, but 7.8% went to the Independent Turkey Party (BTP), a nationalist party. The fact that more parties are fielding candidates in 2024, may work to the CHP’s favor: since CHP is the dominant party in the province, these others, including the AKP, could conceivably divide up the local anti-CHP vote.

- The CHP won by comfortable margins (and the AKP polled in the low 40s) in Bilecik, Çanakkale, Eskişehir,Sinop, and Tekirdağ.[18]

- In Yalova, the CHP won the central municipality in 2019 with 45.9% against the AKP’s 44.4%. The remainder of the vote was split between the HDP (0.9%) and the conservative parties, the Democrat Party (5.9%) and the Saadet Party (1.5%). This was actually a less narrow victory for the CHP than in 2014, when the party’s candidate won by 228 votes. While the trend has been favoring the CHP in recent cycles, this is likely to be a close race in 2024. The Democrat Party is, yet again, running a candidate, but the party’s support seems to be growing smaller with each passing year, which may help the CHP consolidate the anti-AKP vote in the central municipality.

The challenges facing the CHP in 2024 are not insurmountable, but chances are high that a few of these 2019 victories will be reversed. The AKP has fewer such challenges.[19] Moreover, internal CHP tensions have put several strongholds into play. Though Izmir is unlikely to fall to the AKP, the CHP leadership’s decision to replace Izmir’s popular incumbent has caused discontent.[20]

Somewhat ironically, in Hatay, it is the post-Kilicdaroglu leadership’s decision to keep an incumbent that caused controversy. Not only is the CHP mayor of Hatay, Lütfü Savaş, a former AKP member (he switchedparties in 2014), but as a political leader in the province since 2009, his administration oversaw the construction and/or continued toleration of many of the shoddy buildings that collapsed during the 2023 earthquakes, leaving at least 24,000 people dead in his province alone (and likely far more).[21] Savaş’ presence during the earthquake was problematic politically since it implicated CHP administrators along with AKP officials. His re-nomination undermines CHP calls for accountability. After announcing they would re-evaluate Savaş’ nomination, Özel and the CHP leadership decided to keep him in place, thereby acknowledging a problem without solving it.[22]

While a few CHP losses can be expected, Istanbul and Ankara are contests where loses will have real consequences for the party. In Ankara, the CHP incumbent, Mansur Yavaş, is well-positioned to win a second term. With roots in the far-right MHP, he can appeal beyond the CHP’s traditional base of the support. Kurdish voters in Ankara, who might be turned off by his past, are a relatively small portion of the local electorate—the HDP won only 1.1% of the local assembly in 2014 and 2019. Istanbul appears to be more competitive because the divides in the opposition are hard for any single candidate to bridge. There, the HDP won 4% of the municipal assembly in 2019. This difference is even more glaring when looking at the 2023 parliamentary vote: in Ankara, HDP (renamed the “YSP”) and its coalition won 4% of the vote; in Istanbul, they won 12%. Up until 2024, İmamoğlu in Istanbul, like Yavaş in Ankara, has proven to be popular with the anti-AKP factions of the far-right—Meral Akşener, the leader of İYİ, preferred both men to Kılıçdaroğlu for the presidential nomination. Yet İYİ is running candidates in the elections and İmamoğlu’s willingness to associate with Akşener in the past may lead Kurdish voters to support the candidate of DEM (as the HDP-cum-YSP is now, confusingly, calling itself).

Conclusion

Predictions are beside the point; the voters of Turkey will make their choices clear soon enough. The concern, however, is whether that choice will be acknowledged. Many voters fear that the results will be challenged in close races. It is just five years since the Istanbul mayoral election results were overturned (following the AKP’s loss) and rerun due to “irregularities.”[23] And even clear victory provides no assurance that elected leaders will be able to remain in office. It is only sixteen months since İmamoğlu was sentenced to four years in jail and removal from office for suggesting that the officials who decided to rerun his initial 2019 victory were “fools” (ahmak).[24] Pending appeal, that conviction hangs over his head.[25] Should he win the election but be replaced, voters in Istanbul would find themselves in the same position as voters in almost all municipalities won by the HDP in 2019. Of those sixty-five municipalities, the government has removed (and often arrested) the mayors and co-mayors in forty-eight. They have been replaced with “trustees” (kayyum) appointed by the central government.[26]

The Istanbul mayoral election is drawing the lion’s share of analysis and attention—because of the city’s size, its national influence, and the impact of the result on İmamoğlu’s bid for de-facto leadership of the CHP.[27]But, even if İmamoğlu’s CHP organization wins Istanbul, it is the totality of other elections that will shape the political landscape in which he operates. Have voters opposed to Erdogan’s government developed the habit of voting for the “most likely” candidate to defeat the AKP-MHP candidate, or have voters decided to vote for the party they prefer? Parties like İYİ, DEM, Memleket, Saadet, Zafer, and Yeniden Refah are betting on the latter.[28] They do not expect to win by running candidates against the CHP in competitive races. Rather, they have made the calculation that Erdoğan and the AKP are not leaving the political scene anytime soon. Under these circumstances the best option is to demonstrate their relative popularity in the hope of strengthening their bargaining position with Erdogan’s government in the years to come.

* Here and below, “mayoral races” includes metropolitan municipalities and provincial center races.

Of the twenty-one major races won by the CHP, ten—those in bold, listed above—were in municipalities held by the AKP (MHP) since the 2014 elections. Three of these (the ones listed above in red) had previously been won by center-left/left parties in the 2009 elections, meaning that the CHP success in these 2019 races may be more of a “return” to the norm. In other words, those just in bold (the metropolitan municipalities of Adana, Ankara, and Istanbul and the municipal centers of Ardahan, Bilecik, Bolu, and Kırşehir) may be more difficult to hold since they have a longer history of conservative dominance.[29] In fact, in the 2023 presidential race, Erdogan defeated Kılıçdaroğlu in Bilecik, Bolu, Kırşehir, and only narrowly lost in Istanbul and Ankara. Kılıçdaroğlu won the Ardahan and Adana races by comfortable margins.

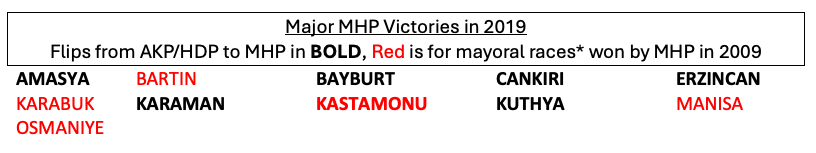

Of the eleven major municipal races won by the MHP in 2019, four have been consistently pro-MHP for multiple election cycles (Bartın, Karabük, Manisa, and Osmaniye); seven had been won by the AKP in 2009 and 2014—the exception is Kastamonu’s central municipality, which the MHP won in 2009. As these eleven races are in conservative provinces, the AKP and MHP generally both run candidates and let the chips fall where they may. Splitting the vote does not risk a left-wing victory (in Kastamonu’s central municipality, for example, the combined AKP-MHP vote is 80%). The 2024 elections promise to be largely the same, with the exceptions of the central municipalities of Erzincan and Bartın, where the AKP is not running candidates this cycle.

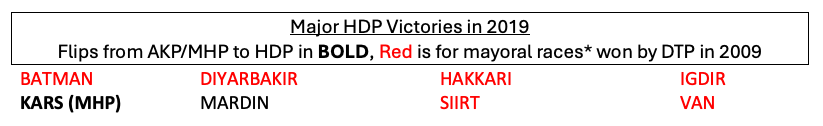

Of the eight major races won by the HDP in 2019, six (those listed above in red) have been reliable for a decade; one (Mardin) seems to have become a stronghold for the left-wing/Kurdish coalition represented by DTP/HDP/YSP/DEM. In Mardin, the 82-year-old Ahmet Türk, a grand-old man of the movement, has been nominated again as mayor in 2024. He was elected in 2014 (52.2%) and 2019 (56.2%) but removed both times—after two years the first time, and five months, the second.[30] Though Türk’s reelection seems likely, the question is whether he will be allowed to stay in office. The most competitive race may be in Kars’s central municipality, where the HDP has been gaining with each election cycle (2009: 14.7%; 2014: 19.4%; 2019: 29.6%). In 2019, the AKP won a plurality of votes for the provincial assembly (and almost 49% if the MHP is included), but Kılıçdaroğlu defeated Erdoğan by a sizeable margin. In 2024, the AKP is not running a candidate, leaving the field open to the MHP candidate, Ötüken Senger, a professor at Kars’ Kafkas University. (This is in-keeping with the MHP tendency to field academicians as candidates.) As in Mardin, the winning HDP candidate in Kars in 2019, Ayhan Bilgen, was removed from office by the government soon into his term; he too is running again. Unlike Türk in Mardin, however, Bilgen has left the party and is running as head of his own party, tacking rightward and further hurting the electoral hopes of the DEM candidate, a retired teacher and party activist named Kenan Karahancı.[31]

Whereas Ağrı and Bitlis are often competitive, Şırnak’s central municipality saw a huge swing to the AKP in 2019 (61.7%, after it received 42.6% in 2009 and 29.3% in 2014).[32] The HDP and newspapers close to the Kurdish movement attribute huge jumps in voter registration in the province either to outright false reporting or to the large number of soldiers, police, and other security forces settled in the province in recent years, following uprisings in 2015-16. (Unsurprisingly, the AKP winner rejects these explanations and points to switches in tribal support.)[33] The HDP-affiliated mayor c. 2015-16, Serhat Kadirhan, was removed and replaced with an official who had recently sought (unsuccessfully) to be an AKP candidate. Kadirhan was arrested in 2021.[34] In 2024, the AKP incumbent, Mehmet Yarka, will be facing, a local DEM party activist. Given the ongoing military presence in the province—possibly in advance of a Turkish military campaign in northern Iraq after the election—another AKP victory in Şırnak seems possible—though Erdogan’s poor showing in the presidential elections suggests the possibility of an upset.[35] The situation in Giresun and Zonguldak seems even less clear. The AKP has been steadily gaining in Zonguldak for several election cycles; the fact that 2019 was an improvement on 2014 despite AKP setbacks in other races across the country suggests another win is likely in 2024. While the same trend is true in Giresun’s central municipality, the gap in 2019 was narrow: 48.8% to 48.4%. In 2024, the AKP incumbent will face off against a local CHP politician (and president of the local football team Sanayispor), whose roots in the small Democratic Left Party (DSP) may help him consolidate the center-left vote.[36]

[1] Ankara mayor Mansur Yavaş seem likely to be reelected due to both his own ability to draw voters across the political spectrum and a scandal involving the extensive property holdings of his AKP opponent, Turgut Altınok, the mayor of Ankara’s Keçiören municipality (Murat Yetkin, “AK Parti Ankara’da havlu atmak üzere, İstanbul’da DEM’den ümitli,” Yekin Report, March 6, 2024; Murat Yetkin, “Başkenti yönetmeye aday Altınok: mirasyedi mi, emlak baronu mu?” Yekin Report, March 21, 2024)

[2] Amberin Zaman, “Meet Kemal Kilicdaroglu …,” Al-Monitor, March 23, 2023; Sinan Ciddi, “Why Did Erdogan Win?” Foundation for Defense of Democracies, May 29, 2023; Berk Esen and Meltem Suat, “Berk Esen: Bu kadar uzun süre partinin başında kalıp oy arttıramıyorsanız gitmeniz gerekir,” daktilo1984, June 4, 2023; “Kılıçdaroğlu’ndan “kaptan” benzetmesiyle CHP’de değişim olacağı sözü,” VOA Türkçe, June 14, 2023. For a very positive account of Kilicdaroglu, see Hakan Yavuz and Ahmet Erdi Öztürk, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu and the New Republican People’s Party in Turkey (Routledge, 2023).

[3] Yunus Anıl Yılmaz, “Kılıçdaroğlu’nun ‘Karar ver’ kampanyasına ait olduğu iddia edilen afişler,” Teyit, May 20, 2023.

[4] For a taste of the politicking following the 2023 elections: Candan Yıldız, “İstanbul’da sürpriz İmamoğlu buluşması,” T24, July 10, 2023; Murat Yetkin, “CHP’de İmamoğlu, muhalifler ve Erdoğan-Gül modeli tartışması,” Yetkin Report, July 13, 2023; “CHP Istanbul chair Kaftancıoğlu to step down from her position,” Gazete Duvar English, July 22, 2024

[5] Halil Karaveli, “Can the New CHP Leader Revive Social Democracy in Turkey?” Turkey Analyst, January 25, 2024

[6] İmamoğlu did not enter CHP organizational politics until the mid-to-late 2000s. Prior to that, he and his family were involved in the center-right ANAP party. His father was the head of the party in Trabzon’s central municipality from 1984-1987 (Özlem Gürses, “Atatürk’e hayranlığı onu CHP üyesi yaptı,” Sözcü, May 30, 2019).

[7] One should also point to the support İmamoğlu received from the CHP provincial party organization led by Canan Kaftancıoğlu—at least until their falling out (“İmamoğlu’nun kampanya direktörünün kitabı, Canan Kaftancıoğlu’nun sert tepkisine yol açtı,” Medyascope, November 6, 2019; “Ekrem İmamoğlu ve Canan Kaftancıoğlu’nun arasındaki …,” BBCTürkçe, December 2, 2022).

[8] For a list of all 2024 candidates for metropolitan municipalities, see HERE; for municipal mayors, see HERE; for town mayors, see HERE (“BÜYÜKŞEHİR BELEDİYE BAŞKANI ADAYLARI,” “İLÇE BELEDİYE BAŞKANI ADAYLARI,” “BELDE BELEDİYE BAŞKANI ADAYLARI,” Yüksek Seçim Kurulu)

[9] In Mersin and Manisa, DEM is not running a candidate (Ayşe Sayın, “Yerel seçimlere 1 ay kala …,” BBCTürkçe, February 28, 2024).

[10] In a number of CHP strongholds, like Çankaya municipality in Anakara (or İzmir, as discussed in footnote [11]), Özel and İmamoğlu have backed close allies and/or Kılıçdaroğlu opponents, which worries commentators like Murtat Yetkin, who thinks these powerplays may stir discontent within the CHP (see Murat Yetkin, “CHP İstanbul’u kaybederse fatura İmamoğlu ve Özel’e çıkar,” Yetkin Report, February 14, 2024; Murat Yetkin, “En geniş ittifak: İmamoğlu’na kaybettirme ittifakı,” Yetkin Report, February 22, 2024; Murat Yetkin, “İmamoğlu kaybederse, Kurum’un başarısı sayesinde olmayacak,” Yetkin Report, March 03, 2024).

[11] In İzmir, mayor Tunç Soyer was not renominated; instead, the mayor of the central Karşıyaka municipality, Cemil Tugay, who hadfavored Kılıçdaroğlu’s removal, was named as the CHP candidate (“Tunç Soyer, beş yıl daha …,” Medyascope, August 31, 2024; “Karşıyaka Belediye Başkanı: CHP yönetimi değişmeli!” Cumhuriyet, September 27, 2023; “Main opposition CHP does not renominate …,” Gazete Duvar English, January 31, 2024).

[12] Aydın (CHP/MHP), Muğla (CHP/MHP), Mersin (CHP/MHP), Tünceli (HDP/CHP), and Iğdır (HDP/MHP). In the major mayoral races (i.e., metropolitan municipalities and provincial centers, the AKP was first or second everywhere except Adana, Osmaniye, Mersin, Manisa, Kırklareli, Tünceli, Kars, and Iğdır.

[13] The only province that the MHP won designated a “metropolitan municipality” was Manisa. This victory meant that the MHP mayor will administer the whole province. The MHP’s other 10 victories, however, were in the provincial centers of provinces, which often contained only between a third and a half of the provinces’ populations. Though the MHP often won a few additional mayoral races in these provinces, it seldom won a majority of the provincial assembly. Even in Manisa, where the MHP’s candidate was allowed to run without an AKP-challenger, the AKP won the most seats in the assembly, followed the CHP.

[14] Throughout this article, I refer to “major elections” as a way of describing both metropolitan municipalities (e.g., Izmir), which are effectively the same as “the province,” and central municipalities (e.g., Tokat), which are only the largest of several municipalities in the province. My calculations of how large a portion of the population victory allows parties to govern are back-of-the-envelope calculations based on Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK) population statistics (see “Adrese Dayalı Nüfus Kayıt Sistemi Sonuçları, 2023 [Tablo 1],” TÜİK and “31 MART 2019 YEREL SEÇİM: Türkiye geneli,” Sözcü).

[15] In fact, we might also count Kırklareli, where a dissident CHP member won the central municipality mayoral race with 37.5% of the vote. He has since rejoined that party and is running again in 2024. His 2019 victory was narrow—the MHP won 35.9%—but this close race was due to the CHP also running an official candidate and winning 21.1%.

[16] For a list of all candidates for metropolitan municipalities in 2019, see HERE; for municipal mayors, see HERE; for town mayors, see HERE (“31 Mart 2019 Mahalli İdareler Genel Seçimleri Büyükşehir Belediye Başkanlığı Seçimi Kesin Aday Listesi,” “31 Mart 2019 Mahalli İdareler Genel Seçimleri İlçe Belediye Başkanlığı Seçimi Kesin Aday Listesi,” and “31 Mart 2019 Mahalli İdareler Genel Seçimleri Belde Belediye Başkanlığı Seçimi Kesin Aday Listesi,” Yüksek Seçim Kurulu).

[17] “Aytaç Durak görevden alındı,” Hürriyet, March 28, 2010; “Aytaç Durak tutuklandı,” NTV, December 27, 2012; “Aytaç Durak’a beraat kararı,” TRTHaber, July 11, 2013; “Aytaç Durak bağımsız adaylık başvurusu yaptı,” AA, February 2, 2014; Ayşe Sayın, “Yerel Seçim 2019: Adana 25 yıl sonra ‘sol’ diyecek mi?,” BBCTürkçe, March 15, 2019; Taner Talaş, “Adana’da Zihni Aldırmaz nasıl FETÖ’cü ilan edildi? Beraata giden yolun hazin öyküsü,” Serbestiyet, June 14, 2021.

[18] Some have suggested that Eskişehir may be competitive due to the retirement of Yılmaz Büyükerşen, the center-left mayor who has governed since 1999 (Gülsen Solaker, “AKP ve CHP’nin kaybetme riski bulunan iller hangileri?” DW, March 12, 2024; Senem Büyüktanır, “Erdoğan’ın ‘Hatay tehdidi’ Eskişehir’de ‘rıza’ üretir mi?” Medyascope, March 12, 2024).

[19] Races where an AKP incumbent could conceivably lose include Balıkesir, Bursa, Giresun, Muş, and Uşak. In the 2023 Erdoğan lost Balıkesir and won narrowly in Uşak. (In Muş he lost province-wide, but actually won in the central municipality.) Balıkesir remains a conservative province but splits within the more secular-nationalist factions (i.e., the İYİ Party-MHP) have changed the balance. In 2009, the AKP-MHP won 77.5% of the vote (albeit in competition, with the MHP winning) and the CHP winning 14%; in 2014, this was 71.3% (with an AKP victory) and the CHP increasing to 25.3%; in 2019, with the CHP deferring to the İYİ Party and the MHP deferring to the AKP, the result was the AKP candidate winning with 47.8% against 46.5% for the İYİ Party candidate (İsmail Ok, who had been the MHP candidate in 2009 and 2014). In 2024, the AKP incumbent will be facing candidates from both the CHP and İYİ; this makes an AKP victory likely. Moreover, it means that Balıkesir may be a stark example of how profoundly running separate candidates has handicapped the opposition. The dynamic in Uşak is similar to Balıkesir in terms of voters’ party preferences. In Bursa, the MHP is less electorally powerful and the MHP-İYİ divide is less meaningful; as a result, the CHP, rather than İYİ ran a candidate in 2019. In 2009 and 2014, the AKP received 47.3% and 49.5% while the CHP won 27% and 28.7%. In 2019, without İYİ (or HDP) running candidates, the CHP won 47%. In 2024, all parties are running candidates, reducing the likelihood of a CHP victory. In the province of Muş, the CHP is not competitive but the DEM party is. Over the last fifteen years, parties representing the Kurdish/left-wing coalition have dominated at the provincial-level (as reflected in their share of the assembly), but the AKP has won the central municipal mayorship. Each cycle, however, the AKP’s margin of victory has been reduced—to 13.3 points in 2009, 7.4 in 2014, 1.3 in 2019. In 2019, however, Şerafettin Yatçı, a MHP candidate running as an independent, took a sizeable bite out of the AKP vote. In 2024, Yatçı is running again, but as an İYİ candidate, which will likely lead to a rerun of the 2019 results.

[21] “Başkan Savaş’ın AK Parti’de başlattığı istifa rüzgarı sürüyor,” Hatay Yaşam, February 15, 2014; “Hatay Cumhuriyet Başsavcısı, 6 Şubat …,” BBCTürkçe, February 2, 2024; Adnan Gümüş, “Depremde Hatay’da ölüm sayısı ne kadar? …,” Evrensel, February 16, 2024.

[22] “Lütfü Savaş kimdir?” Bianet, January 11, 2024; Murat Yetkin, “Halkı hiçe saymanın bir bedeli olacak mı? Hatay örneği,” Yetkin Report, February 06, 2024; “Özgür Özel’den Hatay açıklaması: Lütfü Savaş’a bir alternatif geliştiremedik,” Bianet, February 16, 2024; “CHP, Hatay’da Lütfü Savaş’ın adaylığıyla yola devam ediyor,” BBCTürkçe, February 20, 2024

[23] Oya Armutçu, “İstanbul seçimi iptal edildi… YSK kararı 4’e karşı 7 oyla aldı,” Hürriyet, May 7, 2019; Aylin Sırıklı, Barış Kılıç, Kemal Karadağ, and Mehmet Tosun, “YSK İstanbul seçiminin iptalinin gerekçeli kararını açıkladı,” AA, May 22, 2019

[24] Ali Macit, “İmamoğlu’nun dört yıla kadar hapis cezası istemiyle …,” Medyascope, November 10, 2022; “İmamoğlu 2 yıl 7 ay 15 gün hapis …,” BBCTürkçe, December 14, 2022.

[25] İmamoğlu faces additional cases as well (“Ekrem İmamoğlu hakkında yeni iddianame …,” BBCTürkçe, July 14, 2023).

[26] “Kayyım belediyelerinin çoğunda yıllardır Sayıştay denetimi yok,” Bianet, November 23, 2023. For a report on the kayyum system prepared by the HDP, see “KAYYIM RAPORU (AĞUSTOS 2019 – AĞUSTOS 2020) 1 YILLIK PANORAMA,” HDP (2020); for the government’s characterization of the system circa 2019, see “BELEDİYELERDEKİ KAYYUM SİSTEMİ VE MEVCUT DURUM RAPORU,” Türkiye Cumhuriyeti İçişleri Bakanlığı, 2019.

[27] As the election approaches, pro-AKP media have been promoting a variety of “scandals” involving İmamoğlu and the CHP. What is important to note about these claims, regardless of their truth, is the way they circulate in pro-government media (which is the majority of media) while going wholly unmentioned in media critical of the AKP. Even if the stories are false, ignoring them makes it hard to understand the perspectives of AKP voters (“Ekrem İmamoğlu, 1.5 milyar TL’lik villaların şirketine ait olduğunu kabul etti,” Sabah, March 25, 2024; “Özgür Özel darbeye direnenlere ‘zibidiler’ demişti,” Yeni Şafak, March 27, 2024; Abdulkadir Selvi, “Para kulelerinde oklar İmamoğlu’nu gösteriyor,” Hürriyet, March 27, 2024).

[28] Vahap Coşkun argues that there is a split in the DEM party between leaders like Selahattin Demirtaş, Leyla Zana, and Ahmet Türk, who hope to resume some form of dialogue with the AKP, and those like Tülay Hatimoğulları and Sezai Temelli, who emphasize defeating the AKP-MHP bloc. The PKK leadership, as Murat Yetkin notes, is still emphasizing its desire and ability to keep fighting (Murat Yetkin, “Karayılan’ın savaş ‘müjdesi’ platonik ‘diyalog’ umutları,” Yetkin Report, March 22, 2024; Vahap Coşkun, “DEM Parti’de iki grubun mücadelesi,” Serbestiyet, March 26, 2024).

[29] If you believe polls, the CHP remains on-track to hold Istanbul (“MetroPOLL anketi: Kılıçdaroğlu yüzde 49,1,” Diken, May 11, 2023; Murat Yetkin, “Sencar: ‘İktidar Kurum için değil İmamoğlu için çalışıyor’,” Yetkin Report, March 27, 2024).

[30] Ahmet Türk was replaced in both 2016 and 2019 by Mustafa Yaman. After a series of corruption allegations led to arrests of an associate of Yaman’s nephew, Yaman himself was removed in 2020 and replaced. (“Mardin Büyükşehirde Zeyni Teker yolsuzluktan tutuklandı,” Mardin Haber, November 27, 2020; “Investigation into trustee-run Mardin municipality reveals extent of corruption in tender processes,” Gazete Duvar English, December 22, 2020; “Mardin kayyımına 540 milyonluk yolsuzluk soruşturması,” Gazete Duvar, September 14, 2021).

[31] Mustafa Peköz, “Ayhan Bilgen’in çıkışı ve HDP,” Sendika.org, November 6, 2020; “Ayhan Bilgen, HDP’den istifa etti,” Bianet, December 14, 2021; “Selda Güneysu, “Ayhan Bilgen, AKP’ye kapıları kapatmadı,” Cumhuriyet, March 16, 2023; “MHP Kars Belediye Başkan adayı …,” Cumhuriyet, January 16, 2024.

[32] Since 2009, the AKP vote in Bitlis’ central municipality has fluctuated between 40.4% (2014) and 43.8% (2019) and the HDP/DTP between 44.2% (2014) and 33.1% (2019); this suggests that AKP is more likely to win since the DEM is unlikely to achieve its mid-2010s popularity. Ağrı is highly idiosyncratic with parties of all stripes vying for influence. In 2019, for example, Savcı Sayan won the central municipality race as an AKP candidate despite the fact that he had once been a member of the CHP, closely tied to former party leader Deniz Baykal, a harsh critic of the AKP. Sayan resigned in 2023 to run (unsuccessfully) as an AKP parliamentary candidate in Izmir. In 2024, the DEM party is running Hazal Aras for the central municipality; she was previously elected mayor of Diyadin municipality in 2014 but was removed in 2016. She ran again in 2019 but withdrew before the election. Pro-AKP newspapers continue to accuse her of ties to the PKK, and police continue to investigate her for ties to various Kurdish organizations, all of which suggests she will likely be a target for removal should she win and should the government continue its policy of imposing “trustees” (kayyum) on Kurdish municipalities (“CHP’den ihraç edildi Kılıçdaroğlu’na çattı,” Son Gaste, January 4, 2012; “Eski Diyadin Belediye Başkanı Hazal Aras’a Ev Hapsi !” Kent04, December 3, 2022; Dilhan Dumanoğlu, “Kılıçdaroğlu’nun kadrosu netleşiyor …,” Sabah, March 3, 2023; Şenol Balı, “Ağrı’da seçim kulisleri …,” Artı Gerçek, December 17, 2023; Rona Emekçi, “‘Ağrı’nın dertleri Ağrı Dağı’nın boyunu aşmış’,” Yeni Yaşam, March 26, 2024)

[33] Erdoğan Alayumat, “Seçmen kaydırmada AKP farkı!” Yeni Yaşam, January 10, 2019; Atacan Ak, “AKP Şırnak aday adayının evinde seçmen sayısı arttı,” Artı Gerçek, January 17, 2019; “Yerel Seçim 2019: HDP Doğu ve Güneydoğu’da …,” BBCTürkçe, April 1, 2019; “HDP’li vekil Şırnak’ı neden kaybettiklerini açıkladı,” Rûdaw, April 3, 2019; “AKP’den seçmen kaydırma oyunu,” Sur Ajans, December 21, 2023; “Taşımalı seçmen de AKP’yi kurtaramayacak,” Yeni Özgür Politika, January 10, 2024.

[34] Ari Khalidi, “Turkey seizes another Kurdish city’s municipality, removes elected mayors,” Kurdistan24, November 5, 2016; “Firari eski Belediye Başkanı Serhat Kadirhan yakalandı,” Sözcü, August 20, 2021;

[35] “AK Partili Şırnak Belediye Başkanı Yarka: HDP’den 6 bin oy aldım,” Gazete Duvar, April 4, 2019; Ömer Akın, “Şırnak’ın DEM Partili Eş Başkan Adayı Saltan: Kentin gerçek sahipleri geri döndü,” Politika Haber, February 17, 2024; “DEM Parti’nin programında yasa dışı slogana 6 gözaltı,” Patronlar Dünyası, February 24, 2024; “Erdoğan signals ‘final’ offensive against PKK terrorists in Syria, Iraq,” Daily Sabah, March 19, 2024.

[36] Murat Bayraktar, “‘Daha İyi Bir Takım Kurmak İstiyoruz’,” Yeşil Giresun, June 18, 2023; “CHP Giresun Belediye Başkan adayı …,” Cumhuriyet, January 11, 2024.