By Jack Hayward, Third Year, Biology

A study involving University of Bristol researchers reveals how these winged reptiles, known as Pterosaurs, evolved better flying capabilities.

Pterosaurs first evolved from terrestrial archosaurs, emerging as fliers around 245 million years ago, during a time known as The Triassic Period. Up until now, researchers have had trouble determining how these pterosaurs first evolved flight as the earliest fossils found date to 25 million years after this period.

Shrouded in more mystery, is how the pterosaurs’ flight continued evolving to become more efficient over the 150 million years that they ruled the sky. One theory has suggested that flight improvement may have occurred over short evolutionary bursts- but until now this has been difficult to disprove.

A new study, led by scientists at the University of Reading in association with the Universities of Lincoln and Bristol, aimed to provide us with a greater understanding of pterosaur flight improvement, and answer the question of whether the pterosaurs had an advantage over their ancestors.

Scientists gathered information from the fossil records of 75 pterosaur species, spanning the entire phylogenetic diversity of all known pterosaurs and combined this with a newly developed flight model based on living birds.

The model integrated both gliding and powered flight in order to predict the flight efficiency of pterosaurs. This works well for measuring the flight of extinct species because different pterosaurs would have used the method of flight that best suited their lifestyle. Professor Stuart Humphries, author from the University of Lincoln humorously remarked ‘The laws of physics are some of the few things that haven’t changed over the last 300 million years, so it has been helpful using these to understand the evolution of flight.’

The models revealed that pterosaurs used a staggering 50 per cent less energy when flying, this allowed them to increase in size up to ten times.

Fossils were needed for measurements of wingspan and body size. These measurements allowed the scientists to ‘study long-term evolution in a completely new way by comparing the creatures at different stages of their evolutionary sequence’ according to Professor Chris Venditti, lead author and evolutionary biologist at the University of Reading.

Chris and the team determined that pterosaur flight had improved two-fold over their 150 million-year reign and this evolution was driven by consistent minor improvements over time, instead of sudden evolutionary changes.

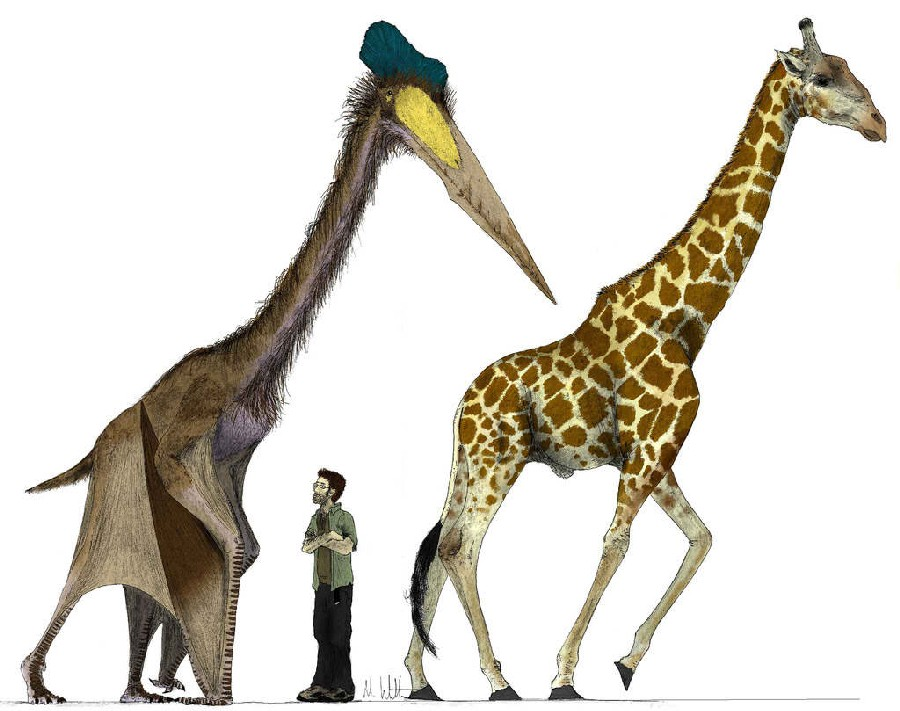

Nevertheless, this improvement in flight was not consistent across all pterosaur species. The azhdarchoid group was an exception. There was previous debate as to how they flew because gigantism and proportionally short wings are identifying characteristics of these species combined. Quetzalcoatlus, for instance, reached the height of a giraffe.

Urban gulls adapt their foraging behaviour to human activity

Bristol researchers bite back at snakebites: the hidden health crisis

The study found that their flight efficiency did not improve over time. Evolutionary biologist Dr Joanna Baker, co-author at University of Reading, has said the azhdarchoids likely spent more time on the ground, and as a result, more efficient flight wasn’t as adaptively necessary. This correlates with the fossil evidence for their terrestrial habits: like their unusually inflexible necks and the trace fossils found of their track marks.

Professor Mike Benton at the University of Bristol remarked: ‘It’s really exciting now to be able to calculate the operational efficiency of extinct animals [using these models], and then compare them through their evolution to see how efficiency has changed.’.

Their findings prove the value newly developed scientific models can add to fossils in solving million-year old mysteries like the evolution of pterosaur flight. ‘We don’t just have to look at fossils with amazement, but can really get to grips with what they tell us.’

Featured Image: Mark Hayward

Are you fascinated by the creatures that roamed the Earth long ago?