Pressure to change: a new donor approach to anti-corruption?

Pressure to change: a new donor approach to anti-corruption?

Phil Mason

Introduction

The evidence has long been clear that corruption is a brake on a country’s chances of achieving sustainable development. It impedes inclusive economic growth and accentuates inequalities; diverts public funds from productive uses; deters inward investment through increasing the costs to, and unpredictabilities for, business; and it corrodes the foundations of accountability and the institutions of rule of law. It also fuels conflict and instability.

Donor programmes to tackle corruption operate in a diverse range of conditions, from stable to fragile or severely conflict-afflicted. Leadership and commitment to tackling corruption varies in intensity and takes different forms: political commitment at the top may fail to bite because of powerful obstruction further down; conversely, islands of integrity can exist within a system in spite of indifference higher up. The scale of citizen and media influence on government varies widely. There are wide-ranging opportunities, currently underplayed, for leveraging change through influencing from the outside in areas beyond aid interventions.

Classical donor approaches rest heavily on ‘capacity building’, working with governing authorities as partners. But more than 25 years of such effort shows little return – for a good reason. In most places where donors work, the governing authorities themselves are distinctly part of the problem. Expecting those who benefit from the status quo actively to assist in organising its demise looks a decidedly optimistic basis on which to build an external donor’s anti-corruption approach.

This blog suggests that the role of incentives (and disincentives) has been underused. Incentivising elites away from corrupt practices (or disincentivising their prevailing behaviours) could be key. Donor programmes need to re-think their strategy, which also means working much more in conjunction with other levers available to their governments.

Current donor strategies

Donor anti-corruption programmes will typically work in many of the following areas to ‘build capacity’ in a ‘partner’ country to tackle corruption:

- Improving civil servants’ skills to manage public funds and deliver services;

- Enhancing oversight of public expenditure through stronger audit systems;

- Creating wider public accountability through data transparency and access to information;

- Promoting integrity in public service, for example through asset declarations and controls on conflicts of interest of officials;

- Strengthening law enforcement and judicial capabilities against corruption;

- Helping to ensure a sound regulatory framework for businesses;

- Fostering free and fair elections, through technical support.

Characteristically, these programmes work through supplying expertise to work alongside the country’s officials. They are predominantly about providing technical training, advice and the wherewithal to ‘do the right thing’. It presupposes that the recipients genuinely want to make such changes. This blog contends that donors’ efforts could have better overall impact if the traditional means were combined with a more systematic approach to working politically.

A stronger approach

The key to securing a genuine step-change would be to ensure that donors address both the technical aspects of the problem (improving the capacity of officials and governments to tackle corruption), and the political incentives for them to do so. Donor agencies predominantly target the former. They can influence some of the latter, such as helping to galvanise citizen voice and demand for accountability, but other parts of a donor’s government could make significant contributions to shifting the incentives of elites and those with whom they do business (for example, the private sector).

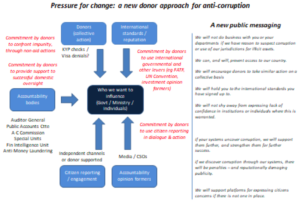

A combination of technical and political interventions, adopted coherently in each location, could significantly change the extent of donor impact. The concept is set out the graphic below.

The proposed approach starts from the premise of working to reduce elites’ room for manoeuvre rather than relying on their ‘political will’ to reform themselves. It seeks to exert multiple pressures, from all directions, accompanied by a scale-up in the public engagement donors seek to have with the government.

‘Bottom up’ pressure is most usually associated with classical donor activity. This involves empowering citizens and relevant groups to hold their authorities better to account.

‘Horizontal’ pressure is also associated with traditional donor assistance, the strengthening of formal state oversight institutions. However, in this model, the commitment is more than technical capacity. It offers the commitment to ensure that the results of strengthened capacities are not lost by weaknesses in another part. For example, this approach would commit to ensuring that an adverse audit finding is seen through to its conclusion, either through law enforcement action or an administrative or judicial outcome. Too often in the past, donors have supported elements of the horizontal accountability network, but not ensured that the good actions of one part are not undermined by weaknesses in another.

The most novel component is the systematic use of non-aid leverage to influence the behaviour of elites and those they do business with, to shift their incentives. One focus would be on the influences that are not in a donors’ direct control but whose impact we could seek to accentuate, for example:

- highlighting reputational effects of corruption on deterring inward investment

- the influence of credit ratings agencies on highlighting corruption risks

- developing strong business opinion and leadership that promotes ‘doing business cleanly’

- the peer pressure possible from regional bodies, such as the African Union, Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), the South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC) and the Commonwealth

- highlighting the negative impacts of being ‘grey-listed’ by the global anti-money laundering review system

- exploiting leverage on ‘international reputation’ generally

A second focus is on the influences that are directly available to a donor’s government, for example:

- decisions on granting/withholding visas to visit the donor country

- greater use of exclusion orders to prevent undesirable representatives of governments coming to the donor country

- financial vetting checks on government representatives (‘know your partner’ checks), and restricting engagement if there is suspicion of corrupt practice

- stronger action on professional enablers (accountants, lawyers, estate agents) in the donor country who facilitate foreign elites to launder stolen funds

- requiring transparency over property ownership by foreign government officials in the donor country

Each ‘recipient’ country would generate a different set of issues that matter to the elite. The step-change would be that donors begin consciously to assess what matters to the elite and develop influencing approaches accordingly. This would require a strong collaborative approach between the donor agency and other parts of its government.

Global and multilateral initiatives on anti-corruption, transparency and accountability could be further vehicles for raising reputational stakes for governments. The Open Government Partnership has the potential to become influential for opening up government processes. The International Budget Partnership and the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency offer similar platforms. These may offer more productive avenues than the formal multilateral system where traditional actors (World Bank, UN) are often constrained in acting in overtly political ways.

Risks and trade-offs

This blog does not consider in full the risks of such an approach. At this stage, the most obvious issues that are likely to arise concern:

- The potential policy tension with other objectives of a donor’s government, in particular trade and wider diplomatic relations

- Any donor implementing such an approach potentially becoming a ‘lone voice’ and isolated

- Possible retaliation from those criticised or under closer inspection

- Appearing to be arbitrary in our actions (especially where a country is endemically corrupt, choices could appear, or be presented, as partisan)

None of these risks are insignificant. Any single donor could encounter major downside threats to its own interests. Arguably, the effectiveness of such an approach will depend on the extent to which it was adopted, in any one country, by multiple donors. This blog seeks to encourage such thinking, and collaboration.

Phil Mason is Senior Anti-corruption Adviser at the Department for International Development, United Kingdom