The U.S. government is compromising democratic values for the sake of maintaining an expensive and ineffective drone base in the West African country of Niger — all while exploring new drone bases in three nearby coastal countries: Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Benin.

The rationale for both the existing base and the aspirational ones is to constrain jihadist insurgencies. The problem is, there’s no publicly available evidence that the base in Niger has done any good. In fact, regional trends — in terms of political violence, but also in terms of overall political instability — suggest that expeditionary counterterrorism does more harm than good.

The U.S. military’s Air Base 201 is situated outside Agadez, northern Niger, and was built in the late 2010s at a cost of some $110 million or more (and upwards of $30 million per year to operate and maintain). Operations began at the site in 2019, involving “intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance” (ISR) drone flights. The New York Times calls it “vital” but it has yet to demonstrate its worth to the public.

During the 2010s, Niger was considered the most reliable Sahelian country in the eyes of Washington, Paris, Berlin, and others. Ruled by an elected civilian, Mahamadou Issoufou (in office 2011-2021), Niger had seemed to be entering a new chapter, leaving behind the coups and rebellions that still plagued neighboring Mali. As crises grew in virtually all of Niger’s neighbors — especially in Libya, Mali, Nigeria, and soon Burkina Faso as well — Niger appeared to be more a victim of spillover violence than of its own homegrown insurgencies.

By 2019, however, it should already have been clear that Niger was brittle — and that France’s assertive counterterrorism operations in Mali were yielding only fleeting gains. In Niger, the 2016 election had been lopsided at best and farcical at worst, with Issoufou’s main opponent, Hama Amadou, spending much of the campaign in detention on shaky charges connected to human trafficking. Niger was also beginning to produce its own militants — and its own spate of human rights abuses by the military. In Mali, France had killed many top jihadist leaders, but violence was only growing. If American airpower was meant to support the tracking of top targets, and if removing those targets did not fundamentally disrupt the insurgencies, then what good was all that surveillance capacity?

Starting in 2020, coup after coup struck the countries of central Sahel. In Mali and soon after in Burkina Faso, coup-makers both channeled and stoked anti-French sentiment, eventually expelling French troops and other Western-backed security missions, such as the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Mali. French counterterrorism ran aground not just at the level of strategy, but also politically. The French failed to maintain the goodwill of populations who cared little if Abdelmalek Droukdel or Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi had been killed when that did nothing against the grassroots fighters, bandits, and ethnic militias that made ordinary people’s lives hellish. Surveillance capacity, moreover, is even less effective when it comes to sorting out who is who at the level of ordinary fighters — just ask the French, who horrified Malians by striking a wedding party at the town of Bounti in January 2019, believing the targets were terrorists.

Niger’s government has been the most recent to fall to a coup, in July 2023. The combination of the coup and the U.S. military’s assets triggered an awkward dance in Washington, as the administration sought — and continues to seek — an impossible balance. On the one hand, there is the imperative to uphold the plain meaning of legal restrictions on U.S. assistance to junta-run countries (a determination the U.S. finally reached in Niger’s case in October). On the other hand, the administration seems to feel compelled to engage the junta with an eye to protecting the drone base. Administration officials have hinted to the junta that if it puts forward even a minimally credible transition plan, the administration will explore ways to restore military cooperation.

The sunk costs of the Niger base appear to be one of the primary arguments in its favor, as well as the argument that the base is vital for counterterrorism success. Yet throwing good money after bad makes little sense, and the argument about counterterrorism is impossible to falsify, given classification practices — and even if all the data were out in the open, backers of unlimited counterterrorism budgets often make the equally unfalsifiable claim that things would be worse without those expenditures. Meanwhile, there is a circularity involved in the logic of the U.S. military presence in Niger as well. As the New York Times puts it, “The American military is still flying unarmed drone surveillance missions to protect its troops posted in Niamey and Agadez” — in other words, the drone base becomes its own justification.

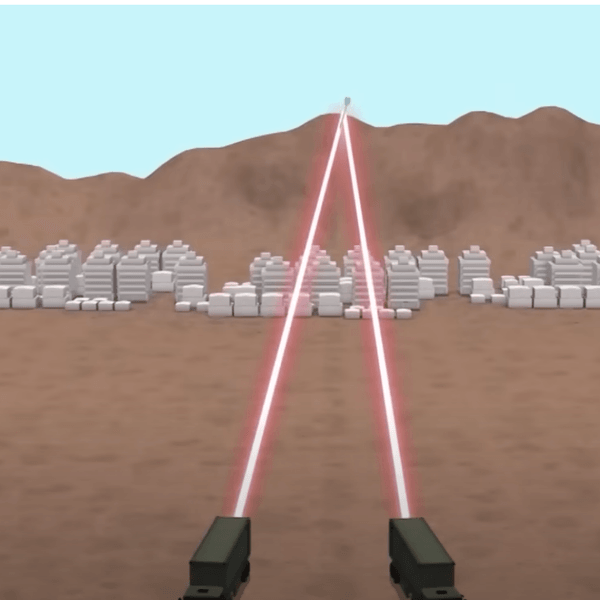

Meanwhile, the U.S. government appears to be simultaneously considering the possibility of maintaining the Niger base and the possibility of shifting resources elsewhere; namely, to Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Benin. The Wall Street Journal reports on “preliminary talks” about opening bases in those countries. The logic, in the Journal’s own words, is as follows: “Drones would allow U.S. forces to conduct aerial surveillance of militant movements along the coast and provide over-the-shoulder tactical advice to local troops during combat operations.”

This logic should sound awfully familiar, as it was the same thinking that has now failed in Niger and beyond. None of the core problems have been solved: whether tracking and killing top leaders translates into wider gains; whether it is possible to distinguish insurgents from non-combatants at the level of rank-and-file fighters; and what the wider theory of change and success is.

Nor has the fundamental political problem been solved or, it seems, even acknowledged: the reference to “over-the-shoulder tactical advice” is very telling. What might seem like a simple military matter is in fact a political one: again and again in the Sahel, it became evident that soldiers often dislike having someone else peering over their shoulder and telling them what to do. All that assistance and advice can also have unintended consequences, as occurred in Niger. It’s not that establishing drone bases in coastal West African countries will inexorably lead to coups — but securitizing the relationship and militarizing those countries’ response to insurgency will only hurt. Cote d’Ivoire has won some acclaim for its response to a nascent insurgency, for example, but more for its social programs than for its combat operations.

And, finally, for U.S. forces, the temptation to do more than peer over the shoulder and whisper into the ear is always there. Best of all would be to wind down the base in Niger, avoid making the same mistakes elsewhere in the region, and keep the Sahel’s juntas at arm’s length.

- Niger was the 'model of stability' in Africa. So what happened? ›

- Rand Paul: Why do we still have troops in Niger? ›

- What will happen to US troops stationed in Niger if the region explodes? ›

- Why the Nigerien junta wants to kick US troops out | Responsible Statecraft ›

![Following a largely preordained election, Vladimir Putin was sworn in last week for another six-year term as president of Russia. Putin’s victory has, of course, been met with accusations of fraud and political interference, factors that help explain his 87.3% vote share. If this continuation of Putin’s 24-year-long hold on power makes one thing clear, it’s that he and his regime will not be going anywhere for the foreseeable future. But, as his war in Ukraine continues with no clear end in sight, what is less clear is how Washington plans to deal with this reality. Experts say Washington needs to start projecting a long-term strategy toward Russia and its war in Ukraine, wielding its political leverage to apply pressure on Putin and push for more diplomacy aimed at ending the conflict. Only by looking beyond short-term solutions can Washington realistically move the needle in Ukraine. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, the U.S. has focused on getting aid to Ukraine to help it win back all of its pre-2014 territory, a goal complicated by Kyiv’s systemic shortages of munitions and manpower. But that response neglects a more strategic approach to the war, according to Andrew Weiss of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, who spoke in a recent panel hosted by Carnegie. “There is a vortex of emergency planning that people have been, unfortunately, sucked into for the better part of two years since the intelligence first arrived in the fall of 2021,” Weiss said. “And so the urgent crowds out the strategic.” Historian Stephen Kotkin, for his part, says preserving Ukraine’s sovereignty is critical. However, the apparent focus on regaining territory, pushed by the U.S., is misguided. “Wars are never about regaining territory. It's about the capacity to fight and the will to fight. And if Russia has the capacity to fight and Ukraine takes back territory, Russia won't stop fighting,” Kotkin said in a podcast on the Wall Street Journal. And it appears Russia does have the capacity. The number of troops and weapons at Russia’s disposal far exceeds Ukraine’s, and Russian leaders spend twice as much on defense as their Ukrainian counterparts. Ukraine will need a continuous supply of aid from the West to continue to match up to Russia. And while aid to Ukraine is important, Kotkin says, so is a clear plan for determining the preferred outcome of the war. The U.S. may be better served by using the significant political leverage it has over Russia to shape a long-term outcome in its favor. George Beebe of the Quincy Institute, which publishes Responsible Statecraft, says that Russia’s primary concerns and interests do not end with Ukraine. Moscow is fundamentally concerned about the NATO alliance and the threat it may pose to Russian internal stability. Negotiations and dialogue about the bounds and limits of NATO and Russia’s powers, therefore, are critical to the broader conflict. This is a process that is not possible without the U.S. and Europe. “That means by definition, we have some leverage,” Beebe says. To this point, Kotkin says the strength of the U.S. and its allies lies in their political influence — where they are much more powerful than Russia — rather than on the battlefield. Leveraging this influence will be a necessary tool in reaching an agreement that is favorable to the West’s interests, “one that protects the United States, protects its allies in Europe, that preserves an independent Ukraine, but also respects Russia's core security interests there.” In Kotkin’s view, this would mean pushing for an armistice that ends the fighting on the ground and preserves Ukrainian sovereignty, meaning not legally acknowledging Russia’s possession of the territory they have taken during the war. Then, negotiations can proceed. Beebe adds that a treaty on how conventional forces can be used in Europe will be important, one that establishes limits on where and how militaries can be deployed. “[Russia] need[s] some understanding with the West about what we're all going to agree to rule out in terms of interference in the other's domestic affairs,” Beebe said. Critical to these objectives is dialogue with Putin, which Beebe says Washington has not done enough to facilitate. U.S. officials have stated publicly that they do not plan to meet with Putin. The U.S. rejected Putin’s most statements of his willingness to negotiate, which he expressed in an interview with Tucker Carlson in February, citing skepticism that Putin has any genuine intentions of ending the war. “Despite Mr. Putin’s words, we have seen no actions to indicate he is interested in ending this war. If he was, he would pull back his forces and stop his ceaseless attacks on Ukraine,” a spokesperson for the White House’s National Security Council said in response. But neither side has been open to serious communication. Biden and Putin haven’t met to engage in meaningful talks about the war since it began, their last meeting taking place before the war began in the summer of 2021 in Geneva. Weiss says the U.S. should make it clear that those lines of communication are open. “Any strategy that involves diplomatic outreach also has to be sort of undergirded by serious resolve and a sense that we're not we're not going anywhere,” Weiss said. An end to the war will be critical to long-term global stability. Russia will remain a significant player on the world stage, Beebe explains, considering it is the world’s largest nuclear power and a leading energy producer. It is therefore ultimately in the U.S. and Europe’s interests to reach a relationship “that combines competitive and cooperative elements, and where we find a way to manage our differences and make sure that they don't spiral into very dangerous military confrontation,” he says. As two major global superpowers, the U.S. and Russia need to find a way to share the world. Only genuine, long-term planning can ensure that Washington will be able to shape that future in its best interests.](https://responsiblestatecraft.org/media-library/following-a-largely-preordained-election-vladimir-putin-was-sworn-in-last-week-for-another-six-year-term-as-president-of-russia.jpg?id=34283894&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C77%2C0%2C77)