Wartime shipwrecks such as the USS Juneau – recently discovered in the Pacific Ocean by philanthropist Paul Allen and his team – are of great interest to both military historians and the general public. The USS Juneau was holed by a Japanese torpedo off the Solomon Islands in November 1942, and sank in more than 13,000 feet of water with the loss of 687 lives. Its discovery offers a hugely valuable insight into the fate of both the ship and its crew.

Many such wrecks lie in extremely deep, relatively clear waters and are the legacy of naval battles fought far out to sea. But some of the technologies and methods that are being used to locate and identify such sites are now being employed by scientists in shallower, sediment-rich UK waters for similar – and very different – purposes.

During both world wars, Britain relied heavily on shipping convoys to supply the nation via well-established maritime routes into major ports such as Liverpool, Cardiff and Bristol. But these busy marine “corridors” were also well known to enemy forces, and losses due to German U-boat attacks, mines and collisions due to enforced “blackouts” in the Irish Sea were significant throughout both conflicts. There are more than 200 such wreck sites around Wales and many have yet to be examined in any great detail.

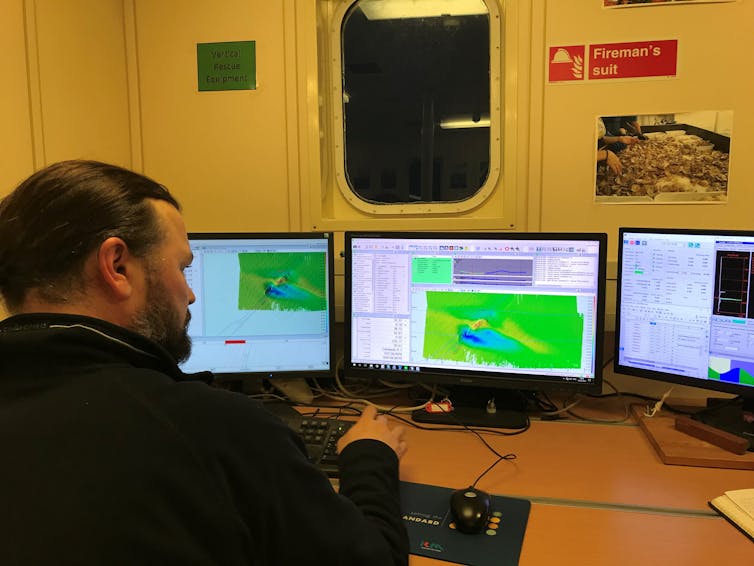

Since 2014, via the SEACAMS project funded by the Wales European Funding Office (WEFO), scientists from the School of Ocean Sciences at Bangor University have been using their research vessel Prince Madog – which is equipped with state-of-the-art multibeam sonar technology – to locate and survey vessels from both world wars. And in the Irish Sea alone, there are plenty to choose from.

How it works

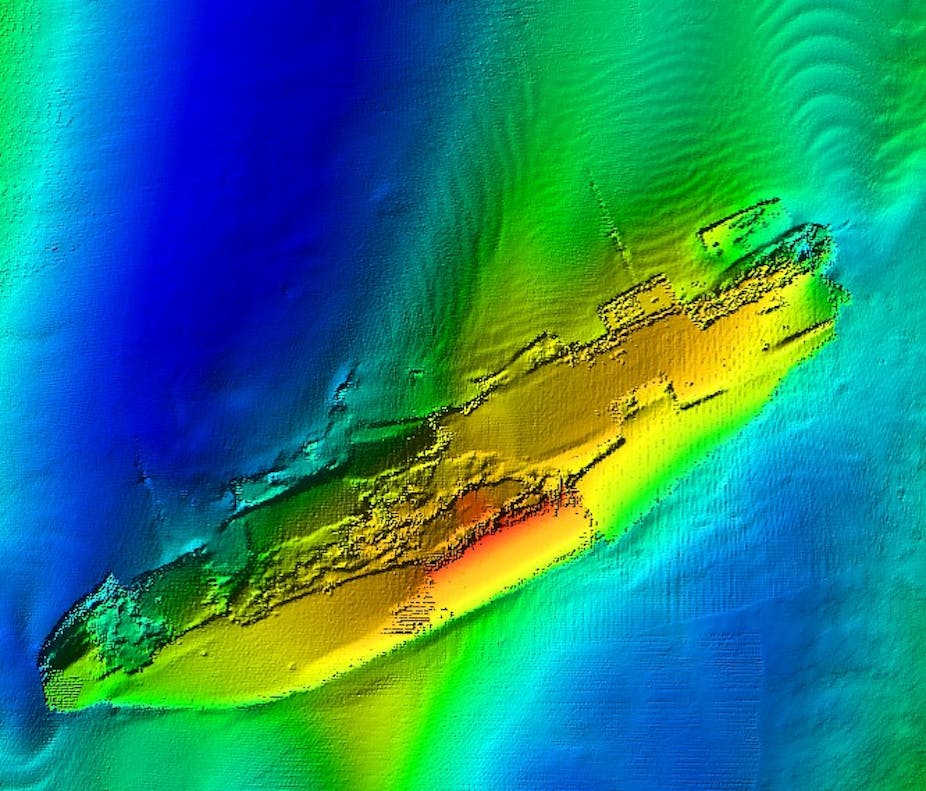

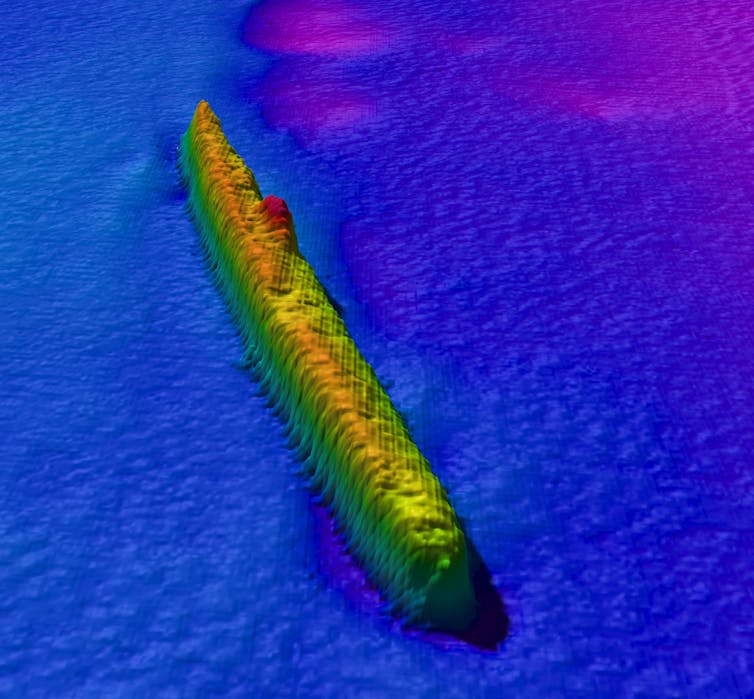

The modern multibeam sonar systems on the Prince Madog generate very high resolution, three-dimensional models of the seafloor as the research vessel moves through the water over it. Depending on conditions and the specific systems used, these models can allow surveyors and scientists to identify objects at near centimetre scale. In water depths of 100 metres, typically found in the Irish Sea, researchers are generating models and images of wrecks that can help marine archaeologists to confirm their identity and even provide evidence of their demise. So far, more than 70 individual sites have been studied and it’s hoped that the project will survey around 100 new wreck sites this year.

While these wartime relics can provide valuable information to historians and archaeologists, they may also help lead to the birth of a new industry. The data being collected are providing scientists with unique insights into how these wrecks influence physical and biological processes in the ocean and this information is now being used to support the ambitions of the marine renewable energy (MRE) sector via research and development projects with developers such as Minesto in North Wales and Wave Hub in Pembrokeshire.

A number of MRE projects –– some being planned, some already underway – aim to capitalise on Wales’ excellent wave and tidal resources to create a sustainable energy supply. To assist in this, scientists at Bangor are now using shipwrecks as models and laboratories for predicting what will happen when key MRE-related infrastructure, such as foundations, turbines and cabling, are placed on the seabed at various locations.

Wrecks provide information on how the tide and currents have removed or deposited sediments and how the presence of these structures on the seabed have influenced these processes over time. Researchers are also looking at how these structures can act as artificial reefs, potentially increasing the number of fish in an area and attracting whales, dolphins and diving birds. Through repeat sonar surveys, the research is also examining how different wrecks are degrading and how these vessels may ultimately pose a risk of pollution to nearby coastlines.

The data gathered will be hugely useful to those behind MRE projects, allowing them to better predict how green energy infrastructure will effect – and be affected by – their undersea locations.

Looking deep

As with the surveys underway in the South Pacific, such as the one that discovered the USS Juneau, the research being conducted in the Irish Sea is also driven by a desire to improve our understanding of past conflicts.

The Heritage Lottery funded project, Commemorating the Forgotten U-boat War around the Welsh Coast, 1914-18, for example, is being led by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales in partnership with Bangor University and the Nautical Archaeology Society. It aims to highlight the fact that not all World War I battles and losses occurred along the Western Front – indeed, many raged within sight and sound of the UK coastline.

They were also truly international incidents. Many of the ships sunk were British, French, Irish, Norwegian, Portuguese and Russian – with crews from all over the world. Many German vessels were sunk, too.

The surveys are also solving scores of mysteries. Of the shipwreck sites in the Irish Sea examined so far, we have found that 40% of the vessels have been incorrectly identified on maps and charts. Using the detailed models produced by the sonar technology – as well as naval archives, shipyard records and a little detective work – we hopefully can ensure these mistakes are corrected and that we know exactly what was sunk where. This will give us a far clearer picture of what now lies beneath the waves – and what such wrecks can tell us about the turbulent past of these oceans.