Health systems strengthening for global health security and universal health coverage: FCDO position paper

Published 14 December 2021

Hauwa’u, aged 25, a mother in northern Nigeria. Credit: Lindsay Mgbor/FCDO

Ministerial Foreword

By Wendy Morton MP, Minister for Europe and Americas with responsibility for global health, Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office

The COVID-19 pandemic is the worst global health crisis in recent history. It has killed more than 5 million people, pushed an estimated 150 million into extreme poverty, and left around a billion undernourished.

Robust healthcare systems, such as our own NHS, have been tested like never before. For countries with more limited resources and weaker health systems, the impact of COVID has been devastating.

Preventable deaths have increased, not just from COVID-19, but due to the widespread disruption to health services that the pandemic has caused.

Lifesaving child vaccine services for example, have been disrupted in more than 70% of countries worldwide.

Even before the pandemic hit, half the world’s population did not have access to the health services they needed.

So delivering the Sustainable Development Goal of universal health coverage by 2030 was always going to be a huge challenge.

With the shockwaves of the pandemic resonating around the world, the challenge of achieving health for all is even greater—but we will not give up.

We are renewing our partnerships with developing countries to build stronger and more inclusive health systems. Systems that take us a step closer to universal health coverage, that are better prepared to deal with pandemics and infectious diseases, and more resilient to climate change.

Progress will require political will, international cooperation, and strong leadership and investment from all partners in all countries.

The UK Government will be at the forefront, harnessing our diplomatic and development know-how to strengthen the alliances needed to improve health globally.

We will champion gender equality and a rights-based approach in all our work to ensure that no one is left behind. By working together, the international community can achieve better health for all.

List of acronyms

| Acronym | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ACT-A | Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| BEIS | Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial strategy |

| BHP | Better Health Programme |

| COP | Conference of the Parties |

| COVAX | COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access Facility |

| Defra | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

| DHIS-2 | District Health Information Software 2 |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| DIT | Department for International Trade |

| DRC | Demographic Republic of Congo |

| EPD | Ending Preventable Deaths |

| EWARS | Early Warning and Reporting System |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office |

| G7 | Group of Seven |

| GHD | Global Health Directorate |

| GHI | Global Health Initiatives |

| GHS | Global Health Security |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HMG | Her Majesty’s Government |

| HMIS | Health Management Information System |

| HSS | Health Systems Strengthening |

| IBRD | International Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

| IDA | International Development Association (World Bank) |

| IHR | International Health Regulations (2005) |

| IR | Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy |

| LICs | Low-Income Countries |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| MoH | Ministry of Health |

| NCD | Non-Communicable Diseases |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organisation |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| ODA | Overseas Development Assistance |

| OGDs | Other Government Departments |

| PHC | Primary Health Care |

| PDP | Product Development Partnership |

| PMNCH | Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health |

| RDB | Regional Development Bank |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SEAH | Sexual Exploitation and Abuse and sexual Harassment |

| SRHR | Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| UHC | Universal Health Coverage |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UKHSA | UK Health Security Agency |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNAIDS | Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS |

| UNFPA | United Nations Family Planning Association |

| UNICEF | United Nations Children’s Fund |

| WaSH | Water, Sanitation and Hygiene |

| WBG | World Bank Group |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Introduction

Good health and wellbeing matter to everyone. We all want to live healthy lives and stay physically and mentally strong. Achieving this means that we can use quality health services whenever we need them, and feel confident, safe, and respected when we use them. Good health is valuable in its own right and brings social and economic benefits. Healthy children can go to school and be in a position to learn, healthy adults can take on meaningful employment and healthy communities can better cope with shocks and crises. Good health and nutrition are the bedrock of resilient, inclusive, secure, stable, and prosperous societies.[footnote 1],[footnote 2] This is why health forms a central part of the globally agreed Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with SDG target 3.8 being to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for all. [footnote 3]

As the COVID-19 pandemic has shown us, investing in global health is in all our interests. The world was ill-prepared for the pandemic and its impact on the global economy has been immense.[footnote 4] It continues to undo years of development. Key economic, human, and social development indicators have stalled and are even reversing as systems have come under strain. It has shown how easily health, social, economic, and political systems can be disrupted. It has also shown how interconnected people, animals and the planet are and highlighted the need for One Health approaches. Progress towards the SDGs was already off-track before the pandemic. Their attainment is now an even bigger challenge.[footnote 5] Building health resilience through stronger health systems must move to the forefront of our collective efforts as we help countries to achieve UHC, strengthen their pandemic preparedness and response capabilities, end the preventable deaths of mothers, babies and children and build healthier, more prosperous, and more resilient populations.

The UK is a longstanding advocate for, and investor in, global health. Investing in health systems remains a key priority for the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and other government departments (OGDs) working on global health. The results of this investment are twofold. A health systems strengthening (HSS) approach not only ensures countries have the capability to prepare for, prevent, detect, and respond to epidemic and pandemic disease outbreaks and health threats like antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and the health impacts of climate change, but also deliver UHC and improve health outcomes for all. Strong, resilient and inclusive health systems are fundamental to delivering the Prime Minister’s Five Point Plan for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, as highlighted in the 2021 Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (IR).[footnote 6],[footnote 7] Strong health systems are essential to the delivery of the G7 Carbis Bay Health Declaration and this government’s manifesto commitments to end the preventable deaths of mothers, babies and children (EPD) and lead the world in tackling Ebola and malaria.[footnote 8],[footnote 9]

This paper is not intended to go into detail on all aspects of the UK’s global health portfolio and it should be read alongside other government strategies, such as the UK’s forthcoming International Development Strategy, the FCDO’s Ending the Preventable Deaths of Mothers, Babies and Children Approach Paper and the Disability Inclusion Strategy. Instead, this paper seeks to outline how the FCDO, in partnership with national governments, will take forward our approach to HSS with greater intention and focus.

Part 1 outlines the importance of strong health systems. It highlights the critical interdependencies between HSS, UHC and global health security (GHS) and why strong and inclusive health systems are critical to realising the international community’s collective global health goals and the SDGs. Part 2 goes on to set out our approach to HSS. It outlines the FCDO’s principles by which we will deliver all our HSS work and highlights particular areas where there is room for us to do more and do better. Part 3 outlines how the FCDO will tackle these challenges through mobilising and coordinating a cross-UK Government approach, strengthened by the broader offer of the new FCDO. It highlights our commitment to work with international, multilateral, national and civil society partners, as well as outlining our approaches to different country and regional contexts to progress, for instance, the systems work that supports cross-border issues such as health security. Before drawing its conclusions, the paper also explains how we will use our health and research investments to support countries to build and sustain more resilient health systems.

Part 1. Why do strong health systems matter?

1.1 Making the case for the strong, resilient health systems that are needed to achieve UHC

Strong, resilient, and inclusive health systems are a critical foundation upon which solutions to the world’s most challenging health issues depend, including reaching the SDG target of UHC. In 2015, the UK joined with 190 other countries to commit to the SDGs. They include SDG 3, ‘to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages’, with the commitment to achieve UHC in every country.[footnote 10] Investing in UHC and health systems makes sense. It improves the health of nations, in turn building human capital and future prosperity. For example, around one quarter of economic growth between 2000 and 2011 in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is estimated to have resulted from improved health outcomes over time.[footnote 11]

UHC is fundamentally about equity, where all people—irrespective of individual characteristics (e.g. wealth, gender, age, geography, ethnicity, disability status etc.)—are able to access safe and quality health services in a timely manner and free from financial burden, as defined in Box 1.[footnote 12]

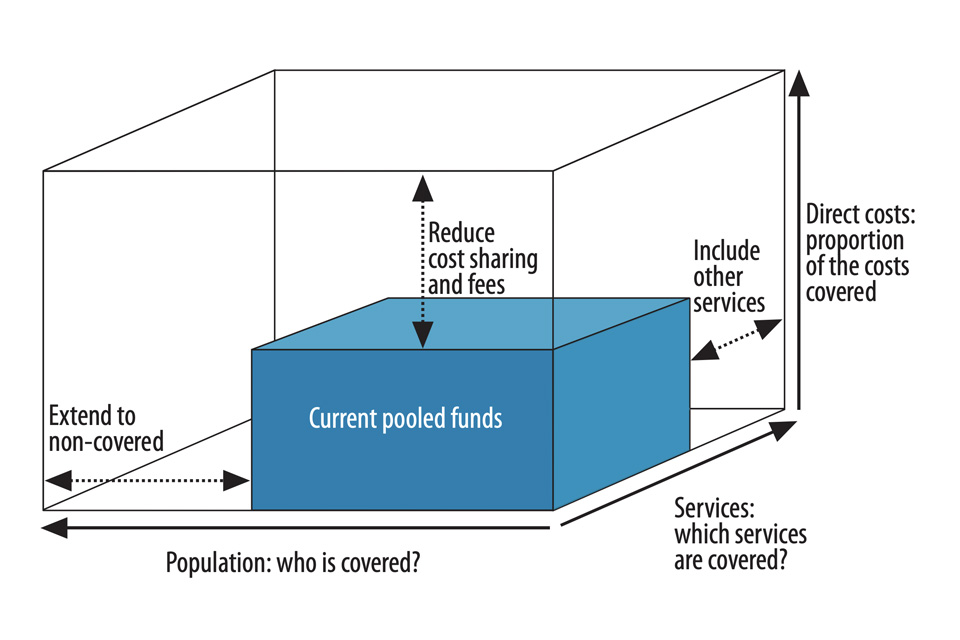

Achieving UHC requires governments to make complex political and policy choices about how to use limited resources. To make it easier to see and understand how to achieve UHC, we talk about three dimensions—often referred to as the UHC cube (see Figure A)—all of which require targeted action by governments and health partners. These dimensions include:1) who is covered by UHC (population); 2) which services are covered and what is their quality (services), and 3) what proportion of people’s health costs are covered (costs) without impacting household financial vulnerability.

Figure A—Three dimensions to consider when moving towards UHC (Source: World Health Organization)

Progress on UHC depends on countries having strong, resilient, inclusive and equitable health systems.[footnote 13] Strong health systems are essential if we are to successfully overcome some of the common barriers to achieving the three core dimensions of UHC to improve health outcomes, including:

-

improving coverage of health services to reach those that currently don’t have access. Only one-third to half of the world’s population is covered by essential health services, and the pace of progress has slowed since 2010.[footnote 14] The poorest communities and people affected by conflict generally face more challenges, with the most marginalised and most vulnerable, including women, adolescents, and people with disabilities, often facing disproportionate barriers to accessing respectful care [footnote 15],[footnote 16],[footnote 17]

-

increasing the quality and package of health services delivered in a more integrated way. More than 8 million people per year in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) die from conditions that should be addressed by their health system. Poor quality care is now at least as significant (and in many cases more significant) as a barrier to reducing mortality as lack of access to services.[footnote 18] Packages of services need to cover a wide range of services that both promote good health through prevention and health promotion and provide treatment (for both physical and mental health), rehabilitation and palliative care. A strong primary health care system is critical to deliver these. Yet services are not always well prioritised, well organised, or sufficiently coordinated or adaptable to reflect the constantly changing burdens of disease and wider causes of ill-health, undermining their effectiveness, and creating inefficiencies and offering less value for money

-

making sure people are not pushed into poverty because of the costs of health services. Many poor and vulnerable people do not seek care due to an inability to pay and/or fall (back) into poverty as the result of the costs of health services. About 930 million people spend more than 10% of their household budget on health care each year, causing financial hardship for many—and the figure is rising.[footnote 19] To help reduce the burden on households and achieve UHC and the associated health targets, governments need to increase spending on, for example, primary health care by at least 1% of gross domestic product. The latest evidence suggests low-income countries (LICs) are still unable to afford an essential package of health services (based on $112 per capita) and on average allocate between $7-9 per capita instead.[footnote 20] As a result, out-of-pocket spending on health can represent more than 40% of some country’s total health expenditures, leaving households vulnerable and countries heavily dependent on external assistance [footnote 21]

-

efforts to build strong health systems for UHC are more important than ever. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have stretched health services across the globe, overwhelming even some of the strongest health systems. In the poorest countries with the weakest systems, health professionals have struggled to respond to the twin burden of COVID-19 response and maintaining essential health service delivery, with coverage of critical health services (e.g. immunisation, prevention and treatment of diarrhoea and malaria, family planning, and safe delivery) falling in many geographies and health inequalities growing the world over.[footnote 22] This is at a time when too many countries are already tackling persistently high rates of maternal, newborn and child mortality and malnutrition, while experiencing substantial rising rates of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer, and health impacts of climate change [footnote 23]

Box 1: What is Universal Health Coverage?

The aim of UHC is for all people and communities to receive the health, nutrition, and water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) services they need without experiencing financial hardship. UHC means that all people can access the full spectrum of quality and inclusive essential services: from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care (such as end-of-life care). UHC also involves highly cost-effective public health measures that prevent ill health, protect the whole population from health threats and provide health security. These include disease surveillance—including linkages to surveillance in the animal health and environment sectors—preventing drug resistant infections, safely managed water and sanitation, addressing unhealthy diets, responding to the health challenges of climate change, and improving air quality.

1.2 Strong, resilient health systems are critical for global health security

Strong, resilient health systems are fundamental to achieving national, regional, and global health security. Global health security (GHS) is centred on preparing, preventing, detecting, and responding to existing and new, emerging public health threats.[footnote 24] WHO defines GHS as “the activities required, both proactive and reactive, to minimize vulnerability to acute public health events that endanger the collective health of populations living across geographical regions and international boundaries”.[footnote 25]

Sustained progress on GHS cannot be made without functioning and resilient health systems capable of protecting all people, including the poorest and most marginalised, from health threats such as infectious diseases, AMR, and the impacts of climate change. Strong health systems, such as routine surveillance, health information, laboratory and immunisation systems, procurement and supply chain management and quality of care, are essential to help prevent, mitigate and respond to these health threats within a country and across borders, strengthening in turn regional and global health security. Having effective systems in place supports and enhances more targeted health security interventions such as implementation of the International Health Regulations (IHR) that are explained below. Taking a One Health approach also contributes to health security (see Box 2) as well as improving multi-sectoral coordination and action.

To improve health security, we need stronger, integrated public health functions that protect people from health threats. Public health functions include a focus on integrated surveillance; response to emergencies; health protection; health promotion and disease prevention.[footnote 26] Public health functions need to be interconnected to animal and environmental services so that health threats are tackled from all angles. A strong public health system also relies on resilient community systems and responses. The COVID-19 response has shown that we know we can strengthen these public health functions, for example, by using genomic sequencing as part of our surveillance systems and by building international cooperation to pool knowledge and the monitoring of likely health threats, using this information ahead of time to rapidly develop new technologies such as vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics.[footnote 27] We can also improve contact tracing and testing by involving communities right from the start, adapting our primary health care systems, strengthening laboratory capacity and developing more interconnected data systems. This will enable policy makers, health professionals and communities to have the latest up-to-date information to inform their decisions about what needs to happen to respond.

To date, 196 countries, including all 194 WHO member states, have committed to improving health security by signing up to the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR). The IHR provide an overarching legal framework that defines countries’ rights and obligations around the handling of public health events and emergencies that have the potential to cross borders. Implementation of, and compliance with, the IHR relies on countries having strong health systems with integrated public health functions.[footnote 28]

Strong health systems are needed now for the rapid rollout of COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics across the globe. New and ambitious COVID-19 coverage targets for vaccinating all adults equitably are necessary, but risk putting fragile health systems under more pressure, adding to the challenge of further outbreaks, and displacing essential health services that have already been affected by the indirect impacts of COVID-19, including routine immunisation. As well as vaccine rollout, health systems need integrated testing and surveillance to manage outbreaks, assess vaccine effectiveness and ensure access to new early treatments to prevent severe disease. We also need to think ahead and be better prepared for the next pandemic. That is why at the UK-hosted G7 Summit in Carbis Bay, the UK—along with the G7 Leaders—supported the ambition to ensure that the world can respond to future pandemics in 100 Days with safe and effective vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics.[footnote 29]This goes hand in hand with the need for countries to have strong health systems that are able to rapidly deploy such new technologies to protect their populations.

Box 2: What a One Health approach can do

The UK sees One Health as referring to two related ideas: first, it is the concept that the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment we live in are inextricably linked and interdependent. Second, it refers to the collaborative and sustained effort of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally, regionally, and globally to attain optimal health for all living things and the ecosystems in which they co-exist.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted poor coordination and collaboration at global and country levels across the human, animal, plant and environment interface. These issues can limit our ability to prevent, detect and respond to new and emerging diseases of epidemic and pandemic potential as well as endemic zoonoses and other challenges including antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Applying an intersectoral One Health approach will ensure that the interlinkages between the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment are accounted for, and can strengthen our approach to global health security as well as contribute more broadly to improved health for people, animals and ecosystems.

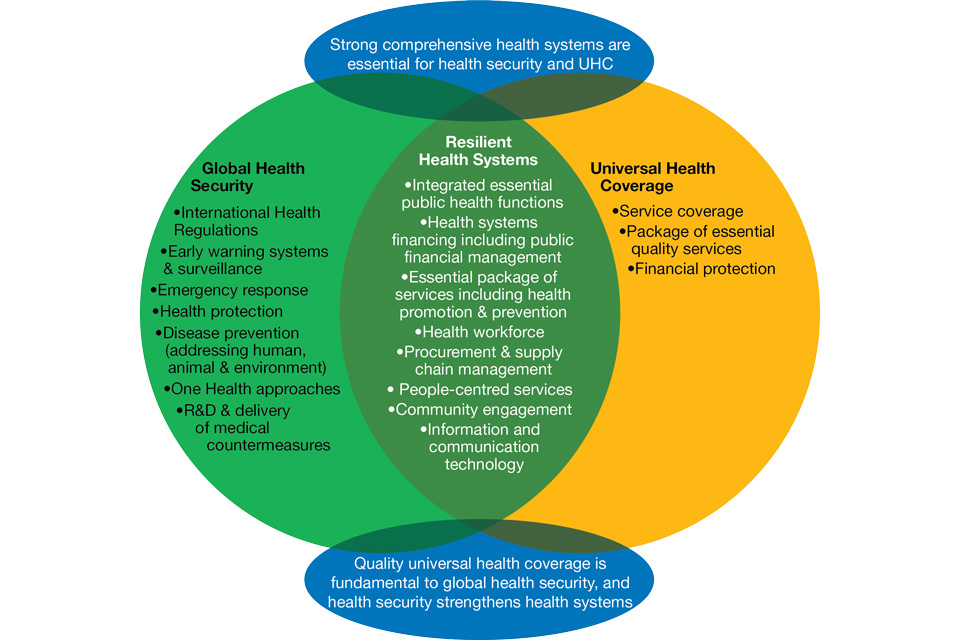

1.3 Health systems: a critical link between UHC and global health security

Strong health systems form the foundation that underpins both UHC and GHS.[footnote 30] UHC and GHS both need strong governance and leadership, motivated health workers, adequate financing, the right medicines, and diagnostics—delivered to the right people in the right places—strong community systems and good data and data systems for decision making. Often it is the same health worker who manages a disease outbreak as it is who immunises a child or provides antenatal care. We often refer to these basic parts of the health system as the building blocks, which are explained in more detail in Section 1.5. These inter-connections between UHC and GHS are illustrated in the diagram in Figure B. We will not improve overall health outcomes without addressing both UHC and GHS at the same time—it is not a case of ‘either/or’. Investments in a health systems approach represents a “double-win”.

1.4 Health systems need to continually adapt to address current and emerging challenges

National efforts to strengthen health systems need to be combined with international efforts to continually adapt to tackle existing and rising health threats including AMR, animal to human spread of diseases (zoonoses), climate change, demographic shifts, and chronic diseases.

- Climate change. WHO describes climate change as the biggest public health threat of the century.[footnote 31] The impact of climate change on health will be increasingly felt through a range of factors including, but not limited to: pollution; extreme weather events; increasing frequency and intensity of heatwaves; water and food insecurity; spikes in acute malnutrition; population displacement; and changing patterns of infectious disease. The resilience of health systems must be built so that they remain effective, efficient, and responsive to the needs of the population in an increasingly unstable and changing climate (see Box 3)

Figure B: How Universal Health Coverage, Global Health Security and Health Systems Strengthening

efforts are interconnected Source: adapted from Wenham C, Katz R, Birungi C, et al. Global health security and universal health coverage: from a marriage of convenience to a strategic, effective partnership. BMJ Global Health, 2019.

-

One Health. Human health is inextricably linked to the health of animals and our shared living ecosystem. We need to find a way to take account of these interlinkages making sure that there is strong collaboration between ministries of health, agriculture and environment alongside partners from those sectors. This “One Health” approach can support .greater health system resilience as well as supporting benefits in other sectors (such as animal health)

-

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Weak health systems increase the risk of AMR and are less able to withstand its effects. Weak supply chains, insufficient regulations, poor infrastructure including inadequate hygiene, water and sanitation services, and lack of healthcare worker training and support can undermine infection prevention and control. Stronger health systems are needed to address the half a million new cases of drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB), growing antimicrobial resistance, as well as resistance to insecticides and antimalarial medicines.[footnote 32], [footnote 33], [footnote 34]

-

demographic changes and increasing urbanisation. Many countries around the world are undergoing rapid demographic change.[footnote 35] In LMICs, where population growth is increasing significantly, there is an increasing shift in people moving to urban areas searching for greater opportunities. These trends are projected to continue with growing speed. The world’s urban areas are highly varied but rapid and unplanned growth of cities can result in different health risks and poorer health outcomes due to a multitude of factors such as, but not limited to, inadequate housing, air pollution, changing diets (often unhealthier), as well as changes to community structures and social support networks. Health systems need to consider and plan for wider demographic changes, addressing the needs of both an ageing population and a growing youth generation (for example in sub-Saharan Africa) and remain adaptable, allowing the right resources to be in the right places, at the right times

-

rising rates of chronic diseases and conditions. Many countries are experiencing a “double disease” burden.[footnote 36] The majority of deaths in LICs continue to be the result of infectious disease, maternal and neonatal disorders, and nutritional deficiencies. However, in all regions, the burden of ill-health caused by NCDs such as cancer, heart disease and diabetes and long-term health conditions, including mental health problems, is increasing.[footnote 37] All forms of malnutrition, including obesity, are escalating globally. Tackling NCDs requires both a strong health system with integrated public health functions and coordinated action across multiple sectors, such as agriculture and the environment.

The health systems we build today need to be fit for purpose to withstand these global challenges. Strong, resilient, and inclusive health systems also play their part in helping societies cope with, and recover from, broader socio-economic changes and shocks. As we progress our health system strengthening work, our approach will have at its centre the need for flexible, adaptable health systems that can effectively detect and respond to change, and we will work in partnership with governments and across sectors to achieve this.

Box 3: Building sustainable climate resilient health systems

Climate change impacts the ability of the health system to serve the health needs of the population. These impacts can directly affect the service delivery infrastructure (human and physical) of the health sector, or its ability to cope with increasing climate related demand for services. It is therefore critically important that health systems are strengthened so that they remain effective, efficient, and responsive to the needs of the population in an increasingly unstable and changing climate.

The impact of the health sector on local air pollution and carbon emissions is also substantial, with up to 5% of the world’s carbon emissions related to health sector activities*. To protect the health of the population, health systems must address both resilience to climate change and its impact on carbon emission.

A global shift toward sustainable climate resilient health systems requires action at both national and global levels. If we are to see tangible change, national governments need to develop plans which address their health system’s current and projected vulnerability to climate change, and which limit the carbon emissions of their health systems. In the UK, the National Health Service in England has shown global leadership on building a health system which strives to be sustainable and low carbon by making a commitment to be net zero by 2045**. Such targets in LMICs must be supported through the international development architecture ensuring that climate and health system strengthening funding and strategic direction are inclusive of sustainable and climate resilient health systems. This cannot be a passive process; global funding mechanisms must be revised to ensure they can deliver on global and local visions. Country commitments through the COP26 Health Programme are a key step to garnering widespread political support.

*Lenzen, M. et al, ‘The environmental footprint of health care: a global assessment’. Lancet Planet Health. 2020 Jul;4(7):e271-e279. Accessed at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(20)30121-2/fulltext

**National Health Service (2020). Delivering a ‘Net Zero’ National Health Service. Accessed at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2020/10/delivering-a-net-zero-national-health-service.pdf

1.5 Building on successful foundations: what does the evidence tell us?

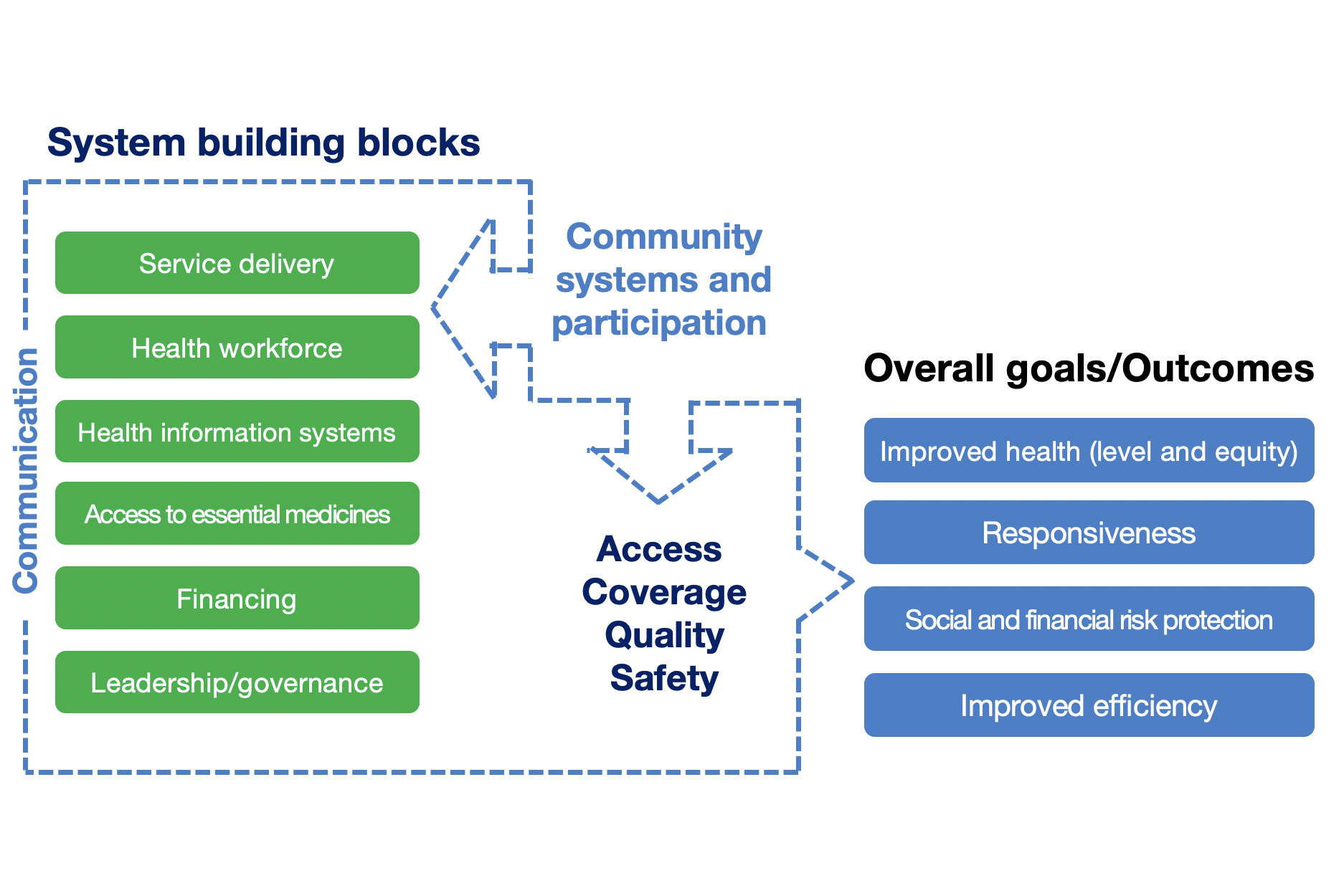

Strengthening health systems is complex, but evidence and past successes show that it is both possible and effective. To help to understand what we mean by a health system strengthening approach, we break the health system down into a number of essential elements that WHO calls the six ‘building blocks’. These work together to make a system function (see Figure C). These are: i) leadership, governance, and accountability mechanisms; ii) health financing; iii) safe, quality, affordable and equitable; iv) human resources for health; v) medical products, vaccines, and supplies; and vi) health information.[footnote 38] The essential role that community systems and communities themselves play is also considered as an important additional health system building block

Figure C: What is a Health System? Source: Adapted from WHO publication (2010)

To build a strong health system, efforts need to be spread across multiple building blocks at multiple levels at the same time. They should be multi-sectoral in nature, with concerted efforts to tackle the wider social and environmental determinants of health (e.g. educational attainment, sexual and reproductive rights, water and sanitation, and nutrition). Two examples of the effectiveness of health system strengthening in practice are shown in Boxes 4 and 5, which show how UK support across multiple health system building blocks is yielding returns in the two contrasting examples of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Ghana respectively. The Ghana example, in particular, demonstrates the broader efficiencies of investing in HSS as the most effective way to use limited domestic resources for the greatest health outcome gains.

The above examples show that health systems strengthening is not something new. The UK and global efforts on health have been either supporting or strengthening health systems for decades. As evidenced in the UHC tracking report, this has resulted in improved coverage of health services in all countries as measured by the UHC index (one of the SDG indicators for health that reflects the coverage dimension of the UHC cube discussed in section 1.1).[footnote 39] This is a collective effort, and we know that the levels of external financing for health systems are important and have increased as outlined in the recent G7 Accountability Working Group report, with funding levels increasing from 38% in 2015 to 47% in 2019.[footnote 40] Yet while progress has been made, we know that more needs to be done and there are things that we, the UK, and the wider global community, need to do differently as we recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and build back better.

Box 4: Using a HSS approach to improve access to health care for 9.5 million people in DRC

The Congolese National Health Development Plan 2019-2022 sets out a path towards UHC, to improve health outcomes of the Congolese people. However, the public health system is unable to provide quality care at scale and the financial barriers for the poor and most vulnerable remain high. An estimated 70% of Congolese have little or no access to health care. DRC is among the ‘top ten’ worst countries for under-five and maternal mortality and 11th in the world for newborn mortality. An estimated 43% of children under five (5.3 million children) suffer from chronic malnutrition. Disease outbreaks including Ebola, measles, and cholera present additional challenges for the overstretched and weak health system.

Women, children and babies receiving community health services and information in St Martyrrs Health Centre, Kasai Central Province. Source: IMA World Health.

The UK-funded programmes Accès aux Soins de Santé Primaires (‘Access to Primary Health Care’) 2013-2019 and Appui au Système de Santé en République Democratic du Congo (‘Support to the health system in the DRC’) 2019-2022 have been designed to support the national UHC strategy and have improved access to health services for around 9.5 million people since 2013. These results have been achieved through a mixed model of direct financing for health service delivery and technical assistance to build system resilience. They include:

-

strengthening national health leadership and management through promoting better coordination, improving public financial management (by providing technical assistance to the Ministry of Health to provide real-time analysis of health spending), better planning, management, and supervision of primary health care

-

establishing new health management information systems (HMIS) and influencing scale-up at national level. The programme designed and tested the HMIS in five provinces has now been scaled-up by the Congolese government in all provinces

-

improving health workers information system through introduction of open-source health workforce information software and training health officials, local data managers and controllers on how to use it

-

strengthening the drug supply chain through training on quantification, supporting the provincial drug distribution centres to improve management, and increasing drug storage capacity in one province

-

ensuring access to care, through financial support to reduce or remove user fees for vulnerable groups, constructing and renovating health centres and hospitals, training staff, and providing essential equipment and products. Improving health equity and prioritising “left behind” groups, through integrating youth-friendly services to promote sexual and reproductive health services

-

tackling underlying drivers of poor health through the provision of community-based water and sanitation services and action to prevent and treat malnutrition

-

engaging communities to encourage the use of health services and to hold service providers to account for delivery, through the development of the national manual for community participation in the management of the health system and use of community scorecards which enable community members to assess quality and access to primary health care

-

applying new digital technologies to improve reporting from remote and inaccessible health centres and improve workforce management

Box 5: The broad and positive impacts of strengthening health systems in Ghana

The FCDO-funded Health Sector Support Programme (HSSP) (2013–2019) worked with the Ghanaian government across multiple areas of the health system to tackle ongoing priority health challenges such as, the growing burden of non-communicable diseases, the threat of AMR, and inequities, including essential health service coverage and quality of care. The programme included technical and earmarked financial assistance to support the Ghana’s Ministry of Health (MoH), utilising a strong partnership approach with UK health organisations, multilateral organisations, and non-government organisations (NGOs). The progress made by this programme directly supported the government’s ‘Ghana Beyond Aid’ agenda and provided a foundation for more effective and efficient use of domestic resources, including through:

-

scaling up community-based health services by nearly doubling the number of community health zones covered from 1,248 in 2014 to 2,320 in 2018, bringing maternal and child health services to an estimated 1.3 million women and children, and reducing the burden on higher level health facilities e.g. district hospitals

-

strengthening the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) who manage the national health insurance scheme that now covers over a third of the population. This involved taking a step-by-step approach: including completing a cost-effectiveness analysis of the national health insurance package; guiding the development of the five-year Health Sector Medium Term Development Plan (2018-2022); and feeding this into Ghana’s UHC Roadmap 2021-2030 that determines the long-term strategic direction for the health sector. The NHIA’s digital capacities have expanded and now automate client registration and payments to healthcare providers creating efficiencies through the national health financing system

-

strengthening health workforce planning in partnership with WHO. This continues to influence staffing decisions and allocation of resources, with MoH estimated savings of 27% that were channelled back into the health budget

-

strengthening national drug regulatory systems through a successful partnership between the Ghana Food and Drug Authority and the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Authority, resulting in Ghana becoming the second regulatory body in Africa to be recognised as part of WHO’s national medicines regulatory system. This has seen increased capacity to determine the quality of drugs and reporting on adverse drug effects, resulting in less substandard and falsified medicines entering the local markets, and most recently enabling Ghana to be the first African country to receive COVID-19 vaccines via the COVAX facility

Part 2. An intensified approach to strengthening health systems

2.1 Building on experience to progress HSS

The UK has long put health systems strengthening at the centre of our international engagement and investments in global health, as part of our strategy to support countries to deliver more health for less both in the immediate and longer term. We are one of the largest government donors for health with a strong track record of bilateral sector-wide health programming, and we have significant domestic expertise to draw on. Our own health system—the National Health Service (NHS)—was established according to the principles of UHC over 70 years ago and is still held up as one of the most effective and equitable health systems globally to this day. Since its inception, the NHS has contributed, alongside other social, environmental, and economic measures, to people in the UK living healthier and longer lives. This—coupled with the UK’s strong leadership and track record on investing in medical research and development—gives us a strong foundation to continue to promote a health systems approach.

We recognise that strengthening health systems is complex and there is no “one size fits all”. We must work in partnership with national governments to support context-appropriate approaches. There is no single intervention that will fix a weak health system and building back better is as much about managing multiple dimensions and interlinkages between the different building blocks (as outlined in Part 1), as it is about working within often highly political environments. That is why we are confident we have the necessary tools that combine our technical and diplomatic skills with our financial overseas development investments to work with countries and partners to tackle the problem from all angles.

As we (the FCDO in collaboration with OGDs) continue to take forward our approach to HSS, there are several principles that will remain fundamental to our work. These are outlined in this section, and are centred around rights-based, people-centred approaches that are inclusive, collaborative, evidence-based and which ‘do no harm’. These principles will be critical as we strive to identify key areas of HSS where we can do more and better. As new evidence has emerged, we recognise that there are still particular areas of our systems strengthening approach that governments and partners, including ourselves, need to change and expand to make progress towards UHC and build stronger health security.[footnote 41] This section identifies some of those areas of the system in need of reform where the UK will increase its efforts. The following and final section of this paper (Part 3) then endeavours to shed light on how the FCDO, in partnership with key departments across government, will turn our approach to HSS into tangible action.

2.2 Key principles at the heart of our HSS approach

FCDO’s overall approach to HSS focuses on supporting efforts to deliver a package of the most cost-effective essential health services to save and improve the lives of the poorest, most marginalised and most vulnerable people in the countries with whom we work.

We intend to do this, by building the overall capacity of the health system (from policy through to delivery) to sustainably deliver over time. The following principles are central to our work:

-

Leaving no one behind by advancing gender equity as well as addressing the needs of all those disadvantaged, including but not limited to the poorest; children and adolescents; people with disabilities; people living in remote or impoverished places; older people; indigenous peoples; refugees and internally displaced persons and migrants; people living in areas affected by complex humanitarian emergencies; and those affected by terrorism (see Box 6). We strive to understand the barriers that affect excluded groups, empower them by strengthening civil action, accountability, and engagement, and include the poorest and most vulnerable within national policy, planning, and service delivery.[footnote 42]

-

Protecting and promoting people’s right to health by promoting the human right to the highest attainable standard of health. We prioritise access to and use of rights-based health information and services for all people, including for the most vulnerable, marginalised, stigmatised and/or excluded groups as outlined in our ‘leave no one behind’ principle. At the heart of FCDO’s approach to strengthening health systems is an understanding of the right to health which respects individuals’ autonomy in relation to their own health, and their ability to have a voice in the system and hold providers and policymakers to account. FCDO supports efforts which address factors such as gender inequality, social norms, discrimination, poverty, laws, and policies which affect all people’s ability to access health services, and their experience of that system when they do.

-

Respecting country leadership and working together by supporting countries to develop and implement their own sustainable national health sector plans according to their priority needs, through collaborative partnerships for capacity building and research. Under the guidance and leadership of national governments, we work to align our contributions to health systems strengthening, UHC and health security as well as with other partner organisations. We also work with civil society to create or strengthen platforms, to better understand barriers to health services and to to promote accountability for inclusion, community engagement and taking a rights-based approach to health.

-

Doing no harm by aiming to deliver real, sustainable benefits to the countries we support. We seek to fully understand the contexts in which we work and use this understanding to minimise the risk of potential harms and maximise our positive impact, while preventing any misuse of funds. Doing no harm refers as much to the ways we design our programmes and partnerships as it does to the way we deliver these. When working in conflict and crisis settings, we aim to respond in a way that contributes to the health system’s resilience over time. We hold ourselves and our partners to high standards of safeguarding against sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment (SEAH).[footnote 43] We aim to integrate SEAH prevention and response strategies into our HSS work through capacity development of health workers to assure safe working environments for all.

-

Being science-led, evidence-based, cost-effective and promoting value for money by ensuring that our programmes are driven by the science and conducted according to the best available evidence. We continue to invest in cutting edge research and evidence, drawing on UK and global expertise and public-private partnerships. Our research ensures that health interventions are data driven and based on the best available science. We work with partner governments to prioritise quality, cost-effective and essential priority health services. The UK is a global leader in science and innovation, and we share both our scientific expertise and the successful innovations with other countries across the globe, to help transform health systems for the future.

Box 6. Leaving No One Behind

Leaving no one behind is critical if we are to eradicate poverty in all its forms, end discrimination and exclusion, and reduce inequalities and vulnerabilities. This means improving access to inclusive essential health services for the most vulnerable and marginalised; people living in poverty, women and girls, people with disabilities and those who are displaced or otherwise affected by crises. It means ensuring that they are empowered to play a meaningful leadership role and their voices are heard in every aspect of our response. A strong, inclusive health system can ensure that no one is left behind through equitable access to affordable and quality essential and specialised health services, without undue financial burden

For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted how people with disabilities are systematically excluded and discriminated against when it comes to access to health services. The UK has a strong track record of global leadership on tackling inequalities, having co-hosted the first Global Disability Summit in 2018, and will feature an inclusive health and COVID-19 recovery pillar in the upcoming refresh of FCDO’s Disability Inclusion Strategy. As we strive to build back better, we must ensure that health systems are inclusive and responsive to the health requirements of people with disabilities in all their diversity.

2.3 Identifying areas of HSS for more concentrated focus

With our UK priorities firmly focused on building back better and ensuring greater health resilience as laid out, for example, in the IR, we have identified a number of areas where the FCDO will focus much of our efforts:

-

integrating key essential services by promoting an affordable mix of equitable, inclusive and evidence-based services that include reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health services, nutrition, communicable and noncommunicable disease control, palliative care, rehabilitation, and mental health. These services need to be delivered based on countries priorities and guided by national leadership, so they become part of a sustainable national package of essential services. These need to be combined with prevention and health promotion services including hygiene practices, safe water and sanitation in health facilities, and transforming the infrastructure so it is more accessible for all and more resilient to climate change, such as investing in clean energy. There is often potential to create greater efficiencies between vertical programmes that focus on single issues (e.g. malaria, TB, HIV, neglected tropical diseases, polio, family planning, etc.) and broader health system efforts, making better use of the limited resources, whilst simultaneously providing a more holistic service which can in turn improve user experiences.

-

strong primary health care (PHC) and community health systems that link to other levels of care effectively. Primary health care is not only the first, but often the only, port of call for communities. This is particularly the case for women and children and the most marginalised and vulnerable, including people with disabilities. Delivering essential services at a primary health care level not only saves lives but is more cost effective. Despite this, primary health care facilities and community systems are not always prioritised, well connected or integrated. Referral pathways between different levels of care are often weak resulting in primary health clinics often managing complicated pregnancies or severely ill patients, when these would be better managed at a district hospital level where there is more access to emergency care if required. Strong primary health care systems provide care in the community and care through the community—meeting individual, family and community health needs. This requires working closely with governments, a broad range of stakeholders and importantly communities themselves, to jointly find solutions to gaps and address weaknesses in the system. Strengthening the primary health care system requires paying attention to the needs of populations, addressing inequalities and inclusion, delivering the quality of services that communities deserve, all while remaining adaptable to meet new and emerging health threats.

-

building resilient public health functions to prevent avoidable illness and strengthen health security by strengthening both national and regional public health institutions and capabilities and working across both human and animal health. This requires an approach that supports governments to work across sectors to build strong health systems that have capacity to implement the IHR and respond to health threats such as COVID-19, AMR, emerging diseases, and climate change. An example of how we already do this is provided in Box 7. Our work will continue to support governments in taking on board a One Health approach, encouraging enhanced cross-sectoral engagement to address threats at the human-animal-environment interface. This requires strong leadership, more coordinated planning, better metrics, strong operating frameworks, and shared prioritisation of efforts

-

more focus on improved quality of care. Improving quality of care and patient safety requires a systematic approach that combines strong planning and continuous, adequately financed quality improvements and assurance across all the elements of the health system, driven by strong leadership. Improving quality of care calls for a stronger interface between health workers and the users of health services, to collectively design and deliver more responsive, people-centred, and respectful services suited to meet community needs. This requires close working with partners, including global initiatives, to support countries to adapt national policies and utilise new tools and guidance on quality of care where these are needed. Key to all of this is our continued support to improve respectful maternity care. More details of how the FCDO will approach quality of care are outlined in our EPD approach paper

-

supporting leadership to realise adequate and sustained health financing by working with finance ministries to encourage increased domestic investment in health and implementation of public financial management reforms, strengthening efficiency and accountability. This is critical for long-term sustainability of the system and progress towards both UHC and health security. This includes supporting health ministries to achieve value for money when allocating health sector budgets to deliver well-prioritised, cost-effective, and transparent packages of essential services that meet the needs of the poorest, most vulnerable and marginalised. External funding, such as bilateral and multilateral aid assistance, will remain important for many countries but needs to be more effectively pooled and better aligned with country priorities and needs

-

strengthening countries’ health and care workforces by aligning our health workforce investments to support national health workforce strategies and priorities. This requires multi-stakeholder efforts driven by national commitment and leadership. This includes recognition of the importance of nurses, midwives and community health workers, strengthening supportive supervision and mentorship and building institutional capabilities to train and equip the next generation of health and care workers. This is an opportunity to bring the FCDO’s education and health offers closer together, also supporting our work on the economic empowerment of girls and women. Our strategies to strengthen the health workforce need to go hand in hand with our efforts on other health system building blocks such as improving domestic financing, strengthening primary health care delivery or strengthening data information systems. We will also continue to ensure that NHS recruitment is done in an ethical manner, following the UK’s Code of Practice on International Recruitment of Health and Care Personnel [footnote 44]

-

working with and for communities. Community engagement and empowerment ensures that services respond to local needs and are: i) of high quality; ii) inclusive, iii) used and trusted by people; iv) that they promote and protect rights; v) and prevent harm.[footnote 45] This requires effective mechanisms for participation, representation, and accountability. As already outlined under primary health care section, working with communities is critical to providing community-led as well as community-based services and information

-

strengthening our multisector approach and engagement by working not only with the public and private health sector but importantly across government sectors to promote a ‘health in all policies’ approach. Many of the actions we will take are outlined in our EPD approach paper. This includes healthy diets and safely managed water and sanitation services, action on climate change and improving air quality. We will continue to ensure our health investments complement and strengthen our support across multiple sectors such as economic development and infrastructure, animal and plant health, climate and environments, food systems, education, addressing violence against women and girls, gender equality, inclusion, and poverty reduction

-

supporting countries to achieve health equity through disaggregating programme data by gender, age, location, and disability status, where possible, and a continued focus on the poorest and most vulnerable groups. This will require close working with countries to strengthen their capacity to collect, analyse and use accurate, disaggregated data, so they can better understand health needs, adapt, and target services where required, monitor progress of health outcomes, and better understand the barriers to accessing health services. This is critical to the success of countries’ national health plans and strategies and to leaving no one behind

-

improving impact measurement by supporting governments to harmonise and optimise their national health information systems, and building institutional capacity to analyse data for better decision making and accountability purposes. We will continue to monitor our own programmes to understand impact and improve ways of working. We will do this for example, through our EPD results framework that incorporates both measurements on health outcomes alongside globally recognised health system related indicators, such as monitoring the UHC Index, IHR scores and benchmarks monitoring financial protection—all outcomes of a stronger health system. Such efforts will be supplemented with additional assessments (operational research, assessments and evaluations) to better understand our contributions to a country or region’s improved system and health outcomes. Furthermore, we will remain accountable on HSS through the G7 accountability framework, which monitors our collective HSS investments, collaboration, and partnership efforts

-

embedding the latest evidence into action and scaling up successful innovations. The work we do in tandem on science and research continues to identify new ways of doing business—from the development of new technologies such as vaccines, to new ways of delivering services e.g. mainstreaming mental health practices. We will continue to work with countries to adopt new innovations as these are developed, assisting them to introduce and scale up those that improve health outcomes and are cost effective

-

transforming health systems by utilising digital technologies as an integral component of more accessible, efficient, and resilient health service delivery. We will monitor innovations in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data, and the internet to assess where these technologies can add value. In line with best practice standards such as the Principles for Digital Development and Principles of Donor Alignment for Digital Health, we will work collaboratively to ensure that digital transformation of health systems is implemented in an inclusive and responsible way, protecting people’s rights, and mitigating against potential harms from misuse of digital technologies [footnote 46]

-

ensuring sustained impact over time by supporting national governments not only to deliver health services today but to build their own capacity to self-finance resilient, equitable and inclusive health systems that both prevent and respond to ill-health and pandemic threats in the future. We need to do better at looking at longer term strategies rather than just focussing on quick wins, acknowledging it can often take years to see the impact of health system strengthening efforts. This will require us to focus on both catalytic, short, and medium interventions, while laying the foundations for long-term action

Box 7: Nepal—Investing in health systems improves health security

The UK has been a long-term supporter of Nepal’s health sector programme that is focused on building a resilient national health system to achieve UHC. UK efforts have focused on working with the government to strengthen many aspects of their health system including health governance, financing, and public financial management; data use for decision making including through digital technologies; quality of care; procurement of medical supplies; design of more climate resilient health infrastructure; and strengthening gender equality and social inclusion. This has contributed to a reduction in maternal mortality (from 539 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 1996 to 239 in 2016) and child mortality (from 50 neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births in 1996 to 21 in 2016).

Maternal and newborn health readiness quality improvement self-assessment by health workers at Baitadi District Hospital, Nepal. Credit: FCDO Nepal Health Sector Support Programme.

Many of these system elements are equally important to prevent, detect and respond to outbreaks and health threats. For example, the UK has supported the Ministry of Health and Population to establish a digital Early Warning and Reporting System (EWARS) that can quickly detect and respond to outbreaks and other public health emergencies such as malaria and severe acute respiratory infections. Over 100 sentinel sites now report using EWARS, drawing upon reports from 8,500 public and private health facilities, using a customized district health information system platform known as District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS-2). The DHIS-2 platform is also used to report on maternal, newborn and child health outcomes but also now includes a COVID-19 module that has assisted Nepal in monitoring and responding quickly to the pandemic. Since 2015, the UK has also helped to modernise the national procurement system for pharmaceutical products and medical equipment used for a wide range of health conditions. Nepal has been able to adapt this quickly to efficiently procure COVID-19 related emergency supplies to respond to the rapid rise in cases. This is being used alongside a stronger accounting and budget control system that is also helping in the financial management of the COVID-19 response.

Part 3. Responding to the challenge: how the UK will turn this into action

3.1 Bringing together our collective UK expertise

The UK is committed to achieving SDG 3 at home and abroad. As part of this commitment, we will build upon existing and new opportunities to strengthen our work on HSS. We will work closely with OGDs to bring together the breadth of UK expertise with a more joined up and combined foreign and development diplomatic presence, covering an expanded geographical footprint. We will use this enhanced offer to refocus and increase our international influence on HSS as we work towards achieving all the health-related SDGs.

As we strive to collaboratively realise this ambition across government, the UK will continue to be a major actor in leading on global health using a health systems and country partnership approach. This will require us to not only focus on technical aspects of health system strengthening but on broader issues of governance and financing. FCDO has created a new Global Health Directorate (GHD) to take this work forward, and, alongside OGDs, to action the Prime Minister’s ambitions for improved global health security and pandemic preparedness and response, as outlined in the IR and supporting the recommendations of the ‘100 Days Mission to respond to future pandemic threats’ report.[footnote 47]

Drawing on the full FCDO network and our wider domestic expertise, we will drive forward our international engagement on HSS in a more coordinated way, enabling us to play a core convening role on the global stage and continue our important influencing and programming efforts at the regional, country, and sub-national level. Our core HSS principles and approaches will spearhead our global health policy and programmes providing the cohesion we need to make sure all the UK’s health messaging and investments across the globe join up, have greater impact, and deliver better value for money.

We will actively mobilise the extensive FCDO and cross-HMG network to seek, sustain and secure stronger relationships with the major global health donors, multilaterals, and stakeholders, to drive commitment to, and investment in, HSS as the backbone to delivering maximum health outcomes and health security for all. The FCDO’s GHD will support these efforts by sharing the latest evidence on what works and ensuring there is available technical and policy expertise on hand if countries need it. We will share our progress using milestones such as the UHC index, and we will continually reflect on lessons learnt from applying our HSS approach so that, as an organisation, we continue to learn and adapt our ways of doing business and tailor our diplomacy efforts.

This will involve our overseas network of offices around the world, including the UK Missions in Geneva and New York as central global health hubs. In doing so, we will step up our work with other development partners to streamline and align our HSS efforts to support countries with the weakest systems. We will further develop our relationships with the new emerging global health donors, as well as providers of health innovations that can benefit all countries, and key players in the rules-based international system.

We recognise that strengthening health systems is not just a priority for FCDO but for the whole of the UK government, as will be reflected in the UK’s upcoming International Development Strategy. The FCDO will continue to work jointly and in close collaboration with other UK government departments particularly the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and we will maximise the comparative advantage of different government departments’ expertise and networks. For example, DHSC, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) already support multiple countries to strengthen their health systems to improve health security and incorporate One Health approaches. We aim to have an even more coherent and efficient ‘One UK Government’ approach to health, where all of UK government departments’ health and health security efforts are better coordinated by the relevant FCDO actors based overseas, to ensure they are aligned with both national health system priorities and the UK’s national interests.

Through our joint UK government efforts, we will strive to strengthen and build mutually beneficial international partnerships—whether in research and development or health system reforms, so we can share the best of our UK expertise, but also learn from other countries’ experiences. We will strengthen these international partnerships where needed to build capabilities in countries, so they result in a win-win for all parties involved. We have already embarked on this journey, and FCDO will continue to work closely with other government departments and agencies, such as Department for International Trade (DIT), the Animal and Plant Health Agency, Healthcare UK, Health Education England, and NHS organisations, to realise the benefits of these mutual and sustainable partnerships in countries where opportunities arise.

We will continue to work closely with important stakeholders such as professional and regulatory bodies, the research community (including research funders), the private sector, NGOs and civil society both in the UK and the countries in which we work. We already work with NGOs in the implementation of many of our health programmes and engage with civil society groups such as Action for Global Health (a group of more than 50 NGO organisations) who inform our HSS policies and practices and who we will continue to meet on a regular basis.[footnote 48] We will continue to listen to representative groups that address inequalities and advocate on behalf of people who are more likely to face exclusion, including but not limited to, women’s and girl’s rights organisations and organisations of persons with disabilities. Together we will use these voices from the ground to inform our future policy direction and implementation of our health programmes.

3.2 Global governance for health

As an already-established leader in global health, we will continue to play our part in getting the global health architecture in the right place to progress a more unified health systems strengthening approach. Using our extensive diplomatic network, we will harness our combined development and diplomatic expertise, leveraging the FCDO’s technical health expertise, strong science offer, and our knowledge and experience in multilateral governance and reform.

We will build on the UK’s 2021 G7 presidency to ensure that we continue to use the important and influential fora, such as the G7 and the G20, to drive forward a health system strengthening approach, as we seek to tackle some of the most challenging global health issues. This includes shaping international discussions on global health security to promote action to develop strong, resilient, and inclusive health systems as the foundation for responding to all health crises whilst embedding a One Health approach. We will continue to use the lessons from the current COVID-19 pandemic reviews to shape and reform governance and financing mechanisms to better support the building of more resilient health systems.

We will also actively seek to bring a HSS lens to conversations on wider international issues, which extend beyond the health sector, for example on climate change. We will build on the themes from the UK’s 2021 COP26 presidency by highlighting and taking action on the important links between global health and climate.[footnote 49] We will do this through focussing on important issues such as climate resilient, sustainable and zero carbon health systems, which are integrated into all hazard multi-sectoral disaster preparedness and response structures.

We will continue to work collaboratively with partner countries and multilaterals including WHO, building important partnerships such as those that have played an integral role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. The UK has been, and will remain, at the forefront of responding globally to COVID-19, including through our significant scientific, technical, and diplomatic engagement and investments in the international response. The UK will continue to play a significant role in shaping the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) and the COVAX facility moving forward.[footnote 50] We want to ensure these platforms enable equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics, reaching high priority groups, but also help us learn how to respond even faster in preparation for future global health crises. We will continue to use our voice to emphasise the critical importance of strong country health system readiness and capacity to roll out new technologies.

Similarly, we will continue to play an active role in existing global coalitions and partnerships and be ready to act where we see new opportunities forming to promote greater health system reforms. For example, we will work with others across the UK Government and beyond to promote strengthened governance and accountability for the Tripartite Plus (WHO, Food and Agriculture Organization, World Organisation for Animal Health and UN Environment Programme) in their global leadership role on One Health, and will use our influence to ensure their work equally supports meaningful progress towards an embedded One Health approach across the four organisations and through regional and country level work. We will continue to work with other coalitions such as UHC2030 and the Partnership on Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH), where we are an active board member.[footnote 51],[footnote 52]

3.3 Making UK investments in multilaterals work for HSS

Strengthening the United Nations collective efforts on HSS

The World Health Organization is the leading global health agency that works with countries to develop plans for their health systems as well as providing both normative guidance and technical assistance to overcome specific health system challenges. As already outlined, our HSS approach will draw heavily on WHO’s technical frameworks. The WHO plays a critical role in coordinating efforts on HSS not just at the global level but more importantly at regional and country level too.

In 2020, the Prime Minister announced new fully flexible UK funding for WHO which will help enable it to deliver its general programme of work, focused on achieving UHC, preventing and responding to health emergencies and threats, and promoting wider health and wellbeing—all using a health system strengthening approach—while accelerating organisational reform.[footnote 53] We will closely work with and track WHO’s performance on HSS through the WHO impact and results framework. We will continue to encourage other donors to align HSS investments to WHO. We will do this through our powerful voice in WHO’s governing bodies, including the Executive Board and World Health Assembly, as well as through our UK-WHO strategic dialogues, our bilateral donor relationships and our ongoing technical engagement with WHO throughout each year.

The UK will also continue to influence the broader United Nations (UN) agencies such as UNICEF, UNFPA and UNAIDS to embed greater systems innovations within their work and to join up their efforts with other partners and across multiple sectors. We will continue to work closely with key international financial institutions such as the World Bank Group (WBG), of which the UK is an influential shareholder, encouraging greater coordination and collaboration with key global health organisations and initiatives such as WHO. The WBG’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and International Development Association (IDA) loans and grants are an important financial mechanism for countries to acquire the resources they need to make their health systems more resilient. We will use our voice and influence through our seat on the World Bank board, and through ongoing negotiations, to ensure there are improved opportunities for countries to use these financial resources to support health system reforms. In a complementary role to the WBG, the Regional Development Banks (RDBs) are trusted partners for many countries and in some cases the largest source of regional finance. We will encourage those RDBs with relevant health expertise and capacity to coordinate with partners and utilise their resources to support health system work.

Working with the Global Health Initiatives (GHIs) to do more on HSS

The UK is among the leading donors of many multilateral and GHIs such as Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Gavi the Vaccine Alliance, and the Global Financing Facility. Our investments to health multilaterals already make a major contribution to health systems strengthening at the country level, as most now have HSS as a strategic objective. Where we fund organisations that are focused on specific diseases or health issues, we will place even stronger emphasis on ensuring that investments are coherent and in line with national priorities and plans for overall health system development and reforms, and not solely focused on singular disease issues. We will reinforce our asks through our influential positions on these organisations’ boards and investor committees, as well as through our engagement with the multilaterals at the country level.

A major focus for all of the UK multilateral investments will be to incentivise greater alignment and join up between all the different organisations and multilaterals that we fund. We will develop our bilateral country programmes alongside the priorities that governments have set and that the multilaterals should align with, to maximise value for money and impact. This may require us and individual agencies to work differently together at global, regional, and country level, for example pooling resources where it makes sense to do so, integrating activities or harmonising ways of doing business. We will also push for greater collaboration, coordination, transparency, and accountability through such initiatives as the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All.[footnote 54] We expect this to reduce duplication of efforts and improve efficiencies and effectiveness from our system investments.

Box 8: What is the EPD approach paper and how does it link to this paper?

In 2019, the UK government committed to stepping up our efforts to end the preventable deaths of mothers, babies and children in low-income countries by 2030. To fulfil this commitment, the FCDO is publishing an EPD approach paper that sets out four key pillars upon which action will be taken. These include a focus on 1) strengthening health systems using the approach outlined in this paper; 2) addressing human rights, gender, and equality; 3) supporting healthier lives and safe environments through better nutrition, access to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene services, improving air quality, and tackling the impacts of climate change; and 4) harnessing new research, technology, and innovations. All of these actions embed a system approach and reinforce the principles and approach outlined in this HSS position paper. We will take action on these issues through a combination of diplomacy at country, regional and global levels; providing technical assistance; investing in multilaterals and through our bilateral programmes; and carrying out research.

3.4 Embedding our HSS approach through our work at country and regional level

Our work at country and regional level will reinforce the work that we do through the multilateral organisations and enhance our globally facing diplomatic and development offer. As already outlined in previous sections, we will use our extensive cadre of health advisers and diplomatic network based at regional and country-level, to strengthen our bilateral partnerships with countries to achieve accelerated health system reforms, linked to our efforts outlined in the EPD approach paper. We will also encourage, support, and engage with multi-sectoral coordination mechanisms between the human health, animal health and environment sectors, including through our professional cadres beyond health (e.g. livelihoods, and climate and environment advisers), to advance the application of a One Health approach at the country and regional levels. We will provide both financial and technical support particularly in Africa and the Indo-Pacific and embed these efforts into our regional and country offices’ plans and strategies.

Our country and regional offer will include a wide range of technical collaboration, including from across the UK government, and we will cooperate in partnership on a given country’s specific needs and demands. This may include providing specialised expertise in a particular technical area, for example to develop health workforce strategies including for midwives, upgrade a national surveillance system, or provide technical assistance to determine an affordable package of essential primary health care services.

Country-level engagement