Lockheed Martin C-130J-30 Hercules. Flickr/Sergey Melkonov. Some rights reserved.Much of the western media has in the past week focused on military successes in the war against ISIS, principally the Syrian army's retaking of Palmyra and the Iraqi army's impending assault on Mosul. Now, two developments add a broader perspective.

First, the Iraqi move towards Mosul is proving more difficult than expected, with units experiencing unexpected opposition in villages on the approach to the city. Second, one of the United States's 'forward fire bases' (FFBs), set up to assist artillery support for Iraqi forces, has itself come under direct attack by ISIS paramilitaries. Fire Base Bell, established in northern Iraq by the Twenty-Sixth Marine Expeditionary Unit, lost one marine, while others were injured. The base has now been "quietly renamed" by the Pentagon, with no public announcement.

These developments indicate three things. Despite the heavy losses inflicted on ISIS by the many hundreds of coalition air-attacks, the group remains resilient. Air-power alone cannot defeat ISIS, yet the limited ground forces now deployed are also vulnerable. And as western governments are determined to avoid thousands of 'boots on the ground', the use of special forces is well nigh certain to increase.

A covert expansion

The last point in turn raises the awkward issue of accountability and the opportunities for public debate on this central element in the expansion of the war – which are notable by their absence. The UK is an outstanding case, for it has special forces operating in Syria, Iraq, Libya and several other countries across the Middle East and northern Africa. British governments of all complexions have for many years maintained secrecy over the deployment of special forces, and it is rare that their presence is even acknowledged.

An inadvertent exception came with the recent comment from King Abdullah of Jordan that the British SAS had been operating in Libya for some months. This apart, information trickles out from time to time, mainly by being fed to journalists on chosen newspapers, especially mass-circulation tabloids (the Mirror and the Mail, for example).

The secrecy is actually at its strongest in parliament itself, where there is a near-blanket refusal to answer any questions on special-force operations. This is especially important when western militaries are becoming more involved in combat against ISIS across the region. Special forces are often at the centre of this new 'shadow war', much as they were in Iraq in 2004-08 when many abuses were, precisely, hidden in these shadows.

There is an additional British element: a substantial expansion in the UK's special forces, not so much regarding the actual numbers at the core – the army’s Special Air Service Regiment (22 SAS) and the navy’s Special Boat Service (SBS) – but more the support elements.

A new briefing from Oxford Research Group – UK Special Forces: Accountability in Shadow War (30 March 2016) – provides a summary of the overall picture. It also points to prime minister David Cameron’s pledge in November 2015 of £2 billion additional investment in special-forces weapons and equipment over the next five years.

A decade ago, 22 SAS had a strength of around 400 troopers, This is unlikely to have risen much beyond 500, and neither has the smaller SBS grown significantly. Instead the increase has occurred in three allied groups.

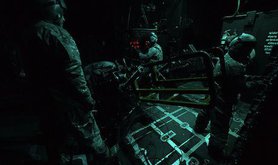

The Special Reconnaissance Regiment (SRR), for example, was formed in 2005 by expanding and developing the army’s 14 Intelligence Company and now has a strength of several hundred, as does the Special Signals Regiment (SSR), founded in the same year. In addition to these is the Joint Special Forces Aviation Wing (SFAW), which is drawn from RAF and army air-corps resources, mainly utilising Chinook and Gazelle helicopters but also the Lockheed Martin C-130J Hercules. The SFAW is likely to be the main recipient of Cameron’s spending commitment.

Perhaps the greatest expansion is the establishment of the Special Forces Support Group (SFSG) based at St Athan in south Wales. This was set up in 2006 and has at its core the first battalion of the Parachute Regiment, which has St Athan as its permanent base. It also incorporates a sizeable Royal Marines contingent and personnel from the RAF regiment. This unusual tri-service group numbers around 800 and provides a range of logistic-support functions in potential or actual conflict-zones, direct support for offensive special-force operations, and training of local personnel.

The total SFSG force is around 800 strong; taken altogether, the SAS, SBS and the four other elements total around 3,000 with the addition of substantial reserve elements, especially for the SAS.

The expansion of British special forces is mirrored by developments in many western countries, including France and Australia. Indeed the US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) is far larger than its equivalent in any allied state; it has almost doubled in the past decade to 70,000 personnel, spread across the army, air force, navy and marine corps.

A worrying repeat

All of this has happened as the conventional 'war on terror', with close to 200,000 boots on the ground in Afghanistan and Iraq, has proved to be such a failure. The threat from ISIS today is every bit as strong as that from al-Qaida more than a decade ago. Moreover, all the indications are that special-force operations will become central to the evolving ground war with ISIS. In countries such as Britain, however, there is as yet almost no opportunity for public or even parliamentary debate.

It could be argued that this does not matter: that if the use of special forces provides enhanced security then so be it. In this view, the government should be trusted and the armed forces allowed to get on with the job. Two considerations suggest otherwise.

The first is that it is dangerous to rely on an assumption that these methods work. The largest set of special-force operations was the shadow war fought by US Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) in Iraq from 2004 onwards. Utilising the US navy’s Seal teams, the army’s Delta Force and Rangers, and the UK’s SAS, the JSOC operation was credited with successfully curbing much of the anti-coalition insurgency. But from the Iraqi survivors of that operation evolved much of the current fighting strength and combat experience of ISIS.

The second consideration concerns the matter of democratic accountability. Three times in the last fourteen years, the public has been told that success was being achieved: with George Bush’s state-of-the-union address in January 2002, his “mission accomplished” speech in May 2003, and on the death of Osama bin-Laden in May 2011. In all three cases the proclaimed triumph proved ephemeral.

Now, it is assumed that a renewed shadow war will do the trick. Yet the public is being denied the opportunity to influence or even discuss the direction of the war. Both in principle and in practice, the seeds of renewed failure are being sown.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.