Many commentators, especially during the 1990s sesquicentenary of the Famine, have broadly characterised the response of post-Famine generations as a form of 'cultural silence'. However, recent research on the history of 'Famine memory' has modulated this view, and explored the many ways Famine appears as subject and reference in political rhetoric, popular and literary fiction, drama, art and visual culture, from the 19th century through to the present.

What's clear is that no singular 'memory' of the Famine exists: it has held different meanings for different groups, at various points in time. The history of the Famine's representation and presence in public space is in fact complex and highly variable. This essay explores public monuments to the Famine as one index of how these cultural meanings and memories have changed over time.

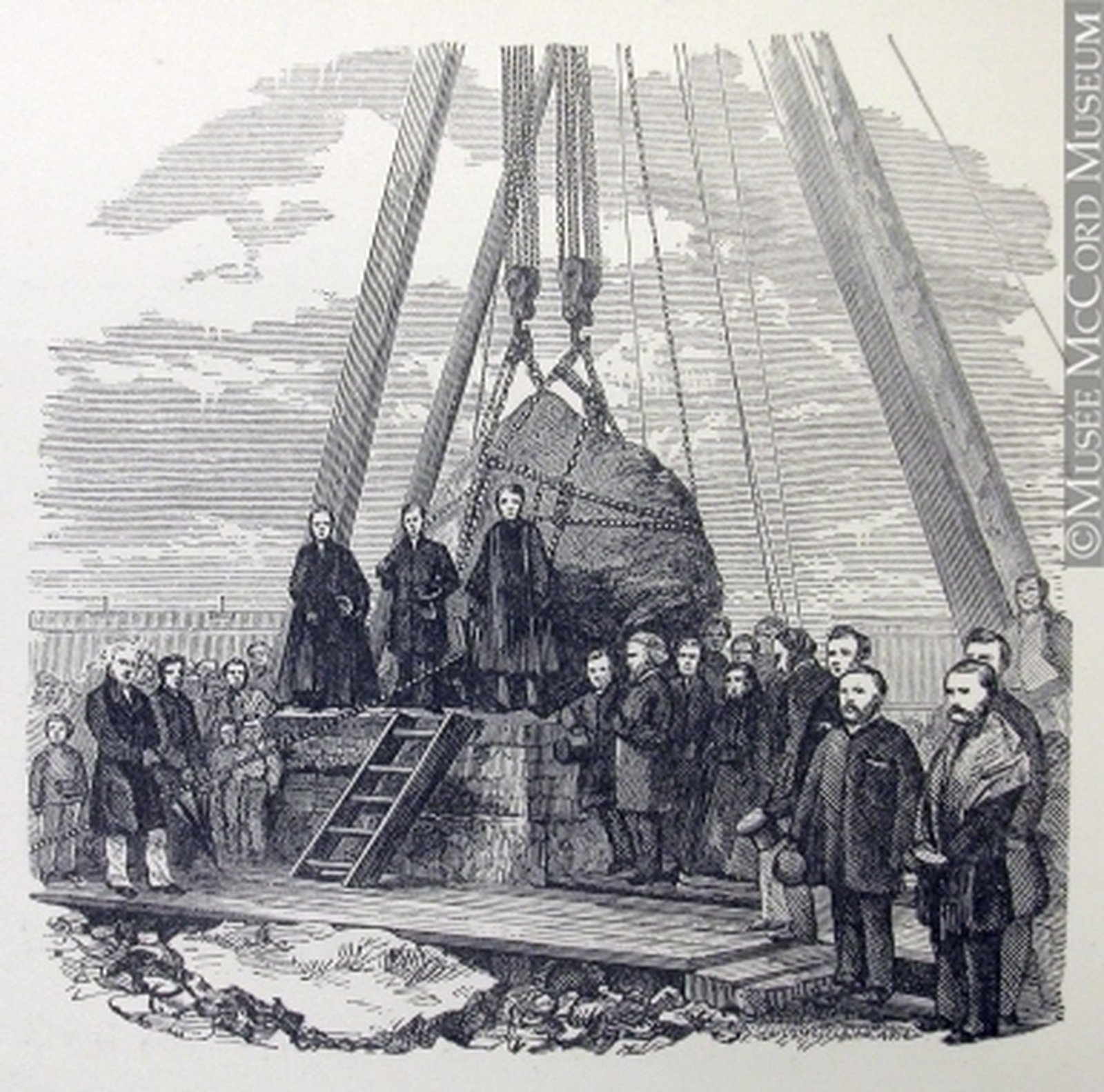

A depiction of the laying of the 'Black Rock' of Montreal, marking the graves of 6000 Irish iimmigrants near Victoria Bridge (1860). Gift of Mr. David Ross McCord. M15934.45 © McCord Museum

The earliest examples of the Famine's monumental commemoration are not in Ireland, but in its diaspora. One of the first was the 'Black Rock' of Montreal, erected in 1859 to mark a mass grave of immigrant victims of typhus uncovered during the construction of Victoria Bridge.

Other early examples include large high cross memorials located on quarantine islands of the eastern Atlantic, including Grosse Île, Quebec (1909) and Partridge Island, Saint John, New Brunswick (1927). Grosse Île holds particular importance as a site of Irish Canadian memory: its complex of quarantine buildings, and numerous memorials (including a contemporary addition in 1998) now constitute the Irish Memorial National Historic Site of Canada.

By contrast, most workhouse Famine mass burial sites in Ireland were neglected throughout the 20th century. Some (such as Carr's Hill Cemetery in Douglas, Co. Cork) continued to be used for burials of suicides and unbaptised infants long after the Famine period, and remained stigmatised and peripheral spaces until recent decades.

Edward Delaney's Famine memorial in St Stephen's Green. Photo: John Crowley

A father explains the meaning of the Famine memorial in St Stephen's Green by Edward Delaney in St Stephen's Green, Dublin. Photo: Getty Images

In the 1940s the centenary of the Famine met a relatively muted response. Despite the persistence of vernacular memories of the Famine – notably evidenced in the Irish Folklore Commission survey on the Famine (1944-5) – very few public memorials were constructed at mid-century.

The fragility of the Irish post-war economy and a reluctance to re-ignite tensions with Britain are two probable reasons for the absence of 'official' response. Nor did the Famine easily conform to existing templates of public commemoration, which privileged individual heroic figures and narratives. Its complex historical legacy, and feelings of shame associated with its memory, also dampened commemorative impulses.

However, the publication of Cecil Woodham-Smith's bestselling book The Great Hunger in 1962 brought Famine history to a wider popular audience than ever before, and a few notable Famine monuments followed in the mid-1960s, including Edward Delaney's Famine group erected in St Stephen's Green in 1967.

From the 1980s NGOs in Ireland, including Concern, Trócaire and Action from Ireland (AfrI), began aligning the memory of the Irish Famine with campaigns for contemporary African Famine relief. AfrI's 'Great Famine Project' launched in 1984 with an annual commemoration that continues into the present.

President Mary Robinson in the 1990s. Robinston frequently mentioned in the Famine during her human rights and diaspora-related work

These efforts heavily influenced the Irish government's establishment of a formal National Famine Commemoration Committee in Ireland in 1994 – an initiative also championed by President Mary Robinson, who referenced the Famine frequently during her human rights and diasporic outreach activities at the time.

These activities pre-empted the unprecedented wave of international commemoration of the Irish Famine which unfolded from the 1990s through to the 2000s, yielding an incredibly diverse landscape of public monuments at all scales.

The National Famine Memorial in Mayo. Photo: Getty Images

Whilst the Irish National Famine Commemoration Committee sponsored an important range of high-profile projects – including the National Famine Memorial in Co. Mayo (1997) and a fund for graveyard renovations – for the most part the 1990s commemoration of the Famine was a grassroots activity.

It was primarily spearheaded and funded by small collectives and individuals across Ireland and its diaspora, sometimes with assistance from local authorities.

In Ireland, much of this work was centred around restoring Famine graveyards, generally in rural locations, often with the inclusion of a new marker or public sculpture. Examples of reclaimed burial sites can be found in Sligo at the rear of St John's Hospital, the former workhouse (1997); in Ring Co. Waterford at the Reilig an tSléibe Famine Graveyard (1996); and dozens more.

The Famine Memorial Garden at Scart, Kennedy Park, Roscrea. In the foreground is the memorial cross designed by Tommy Madden while the focal point of the garden is the cut stone doorway of the Roscrea workhouse which was carefully removed from its original site and stored in Thurles while the remaining buildings were being demolished. Photo: Frank Coyne

Some commissioned urban public sculpture also appeared, such as Limerick's Broken Heart sculpture on Steamboat Quay (1997) and Famine (1997) on Custom House Quay in Dublin.

The 1997 Famine memorial on Custom House Quay

In Northern Ireland the coincidence of the sesquicentenary with the peace process made public commemoration a more delicate and potentially fraught undertaking: a much smaller number of gravesite and other memorials appeared, but works of note include the Enniskillen,Co Fermanagh, memorial (a cross-border project, unveiled in 1996) and the commemorative window installed in Belfast City Hall (1999).

The Famine window in Belfast City Hall. Photo: Godong/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

In Britain public monuments were constructed in Liverpool (1998), Carfin, outside Glasgow (2001), Islay (2000) and Cardiff (2002). Canadian memorials also appeared in Kingston Ontario (numerous, from late 1990s-early 2000s), Saint John New Brunswick (1994/7), Quebec (2000), and Toronto (2007). Australian monuments were unveiled in Melbourne (1998) and Sydney (1999).

A view of the famine memorial at Ireland Park in Toronto. Photo: Bernard Weil/Toronto Star via Getty Images

The largest number of public Famine monuments outside Ireland was constructed in the US, including local examples such as Olean NY (2000) and Phoenix AZ (1999); and large multi-million dollar public art projects in Boston (1998), NYC (2002), and Philadelphia (2003).

The majority of these diasporic projects were commissioned public sculptures, ranging from figurative bronzes to high crosses to contemporary artworks. Many involved the participation of local diasporic groups such as the Ancient Order of Hibernians, and most were funded through private philanthropy and individual donations.

The Irish Hunger Memorial in Battery Park, New York, designed by Brian Tolle and opened in 2002.

Although Famine memorials have primarily tended towards artistic conservatism in their form, several acclaimed public artworks (notably in Sydney, NYC, Dublin and Murrisk Co Mayo) were also produced. In total, more than 100 public monuments were constructed internationally over a ten year period, between 1995-2005, and dozens more have since appeared.

In 2009 an annual Famine Commemoration Day was established by the Irish government, and continues to take place annually at a twinned Irish and diasporic location.

What precipitated this resurgence of attention to the Famine? The economic boom of the 'Celtic Tiger' in 1990s Ireland; a renewed attention to the diaspora in Irish government affairs; and the proliferation of new Famine scholarship throughout the 1990s – 2000s all form part of this, while an observable heightened increase in forms of commemoration worldwide also undoubtedly had an effect.

A remarkable outcome of the Famine's international commemoration was the extent to which it was often tied to other politics and local particulars: the linkage of Melbourne's Famine monument with dispossessed aboriginal communities, or Swinford Co Mayo's memorial (1994) that depicts Gandhi and Michael Davitt side-by-side, are but two examples.

Another view of the National Famine Memorial in Mayo. Photo: Eye Ubiquitous/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

This interest in commemorating the Famine has yet to abate: recent memorials have been erected in Eugene CA (2016), Midleton Co Cork (2017), and Glasgow (2018). Public interest in Famine heritage shows no sign of waning, and has acquired new relevance in the wake of contemporary crises of migration, and confrontations with Ireland's dark and troubled histories currently enfolding as part of the Decade of Centenaries (2012-22).

Ultimately, whether humble or at large scale, commemorative monuments offer unique insights into the interplay between Irish history, heritage, memory and meaning. They remind us that the making of memory has a history of its own, and that the Famine past continues to hold profound meaning for people in the present.

This piece is part of the Great Irish Famine project coordinated by UCC and based on the Atlas of the Great Irish Famine. Its contents do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ.