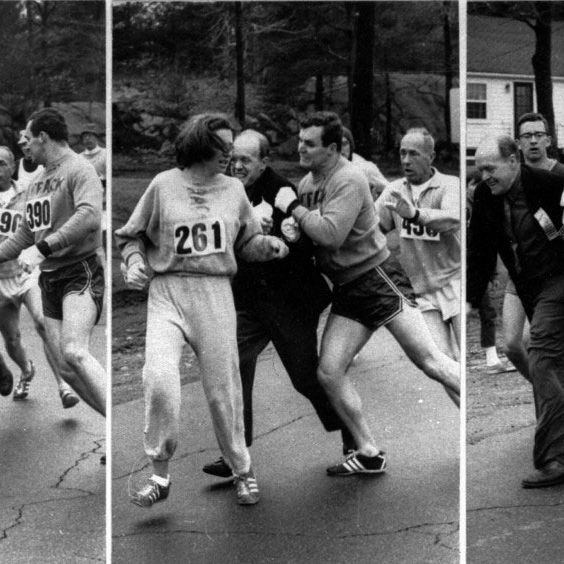

Jock Semple is best remembered as the apparent madman who chased after Kathrine Switzer 50 years ago in the 1967 Boston Marathon. He was trying to rip off her numbers, as Amateur Athletic Union rules did not allow women to enter officially. But there is more to the story. Semple was born in Scotland, immigrated to the U.S., ran Boston a handful of times himself (with a best of 2:45:09 in 1947), and then served as volunteer race director through much of the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s. Without his energy and passion, the Boston Marathon might not have survived the lean years after World War II. Here, a number of veteran Boston runners remember the man in full.

Kathrine Switzer, 1967 Boston Marathon finisher, author, TV commentator, race director, and founder of 261Fearless.org

By the time I got to Heartbreak Hill in the 1967 Boston Marathon, I realized Jock Semple was just an over-worked race director protecting his event from people he thought were not serious about running. Sure, he was notorious for his bad temper. And, sure, he was a product of his time and thought women shouldn't be running marathons. But I wanted to prove him wrong on that point.

Thus it was really Jock who gave me the inspiration to create more running opportunities for women. Almost every day of my life I thank him for attacking me, because he gave me this spark. Plus, he gave the world one of the most galvanizing photos in the women's rights movement. Sometimes the worst things in your life can become the best things.

Bobbi Gibb, first woman to finish the Boston Marathon in 1966, ’67, and ’68

After I finished the Boston Marathon in 1966, some kind soul draped a wool blanket over my shoulders. Several days later, my mother and I realized we still had it at our house. We went to Jock’s office in the old Boston Garden to return it and talked for a long time. We talked about my grandfather, who was Scottish like Jock. He wasn’t hostile at all. Years later, he said he had seen me running without a number, so it was no problem at all.

Jock had great respect for women athletes. He said his mother was a good athlete in her day. The Boston Marathon was his life, and he was just trying to protect its integrity when he saw Kathrine’s number in 1967. I started up in the front row that year. Everyone was chatting happily with me—the officials, the press. No problem. I didn’t have a number and no one tried to stop me. I just stood on the side of the road and waited for half the field to go past me so I could fall in with runners going at my pace.

Bill Rodgers, four-time Boston Marathon winner (1975, 1978, 1979, 1980)

Jock recruited me to run for the BAA in my first Boston in 1973, which I dropped out of. He was just about the only one supporting the marathon at the time. His role was key. After I won in 1975, I was invited to give a talk at Ashland High School. I didn’t own a sports jacket at the time, so Jock took me to a tailor friend of his and bought me a jacket. I still have it to this day.

It was too bad that Jock was saddled with the responsibility of ensuring amateurism in the Boston Marathon, the same as keeping women out. I’m glad Jock became friends with many of the early women runners once the wrong-minded rules were changed. He only wanted to preserve the seriousness of the Boston Marathon.

Sara Mae Berman, three-time women’s winner at the Boston Marathon (1979, 1980, ’81)

Jock was a crusty old Scotsman with great loyalties to the BAA Marathon and to road running in New England. I started running New England races in 1964, so I saw a lot of him. Running was a serious business to him. He knew what discipline and devotion it took, so he felt it demanded respect.

When I started running the Boston Marathon in 1969, I had no trouble from him. He knew I had “paid my dues” in training and racing. It was the beer bellies who snuck up to the front on the starting line that really bothered him. The crass publicity seekers. When he saw Kathrine Switzer with a number, he figured it was just another publicity stunt. Plus, Jock and Will Cloney [BAA president] didn’t want their race to lose accreditation for allowing an illegal runner to race.

Journalist and book author Hal Higdon finished fifth in 1964 in 2:21:55

When I arrived in Boston for my first marathons, Jock Semple was the main man, but also (on the surface) a mean man. He was a little scary when you first encountered him. But Jock was only protecting his race—and it was “his” race—from poseurs who lit cigars on the starting line or dressed in King Kong costumes.

On business trips to Boston, I sometimes visited Jock’s corner at the Boston Garden, where he served as trainer for the Bruins and Celtics. Famous athletes from Bobby Orr to Bill Russell wandered in and out of Jock’s corner, but they were secondary in his mind to a John Kelley or even a Hal Higdon when we stopped by. We were runners, and Jock loved runners most of all. We were his people.

James Green ran for the BAA for 48 years and considers himself “still spiritually a member.” He finished third at Boston in 1960 in 2:23:37

Jock Semple was the most pragmatic ideologue you could ever meet. He was a man of strict principle, but after a severe “moral” struggle, he could change. Witness the Switzer case, and his later support for women runners. He was unyielding and explosive when his runners were involved. He had many tangles with local police because he didn’t believe speed limits and traffic lights applied to him when he was driving race courses to support his BAA runners.

He was blunt, and fiercely loyal to the sport. He was also deeply modest. I never remember him mentioning the great professional athletes and marathon runners who used his therapy services. Jock was the most ethical man I knew. He didn't drink, smoke, or cuss, and was extremely frugal in his habits. He was a good friend, coach, and inspiration.

Nina Kuscsik, first official women’s division winner of Boston Marathon in 1972

My first marathon ever was the Boston Marathon in 1969. I met Jock Semple either at the finish or in the cafeteria. He checked in with me to see if I had a good run and told me to get some of the delicious beef stew. Over the years, it was always good to see Jock and receive such a nice, friendly greeting from him. He took the time even though he was busy with race responsibilities.

Jack Fultz won the 1976 Boston Marathon and has a PR of 2:11:18

In 1972, Jock Semple threatened to toss me out of his race, too. I had finished 12th the previous year, and probably would have been given number “12” except I didn’t decide to run until the last minute. So they gave me whatever number they had left, something like XX1234. When Jock and his prerace tunnel vision spotted that number on the front row in Hopkinton, all hell broke loose. He grabbed my arm and yelled in his gruffest Scottish brogue, “Git en tha back or I’ll kick ya out o tha race! Ya don belong heah!” It took the help of several runners around me to calm Jock down to the point where he recognized me. Jock was absolutely adamant about assuring the integrity of the Boston Marathon. For that we runners loved, admired, and respected him in return.

Charlotte Lettis Richardson, pioneer New England road racer, ran a 3:08:54 marathon in 1974

Jock was an old school runner, running enthusiast, supporter, and trainer. He initially did not like the addition of women to distance races. He once stopped me from crossing the finish line of a cross-country race in Boston. But after he realized we were serious and tough, he came to accept us and support us. He apologized to me later in my career and shook my hand. I honor his memory because he admitted he was wrong about women in running. He was able to say he was sorry and to admit he had made mistakes. That takes courage, and it showed his true character.

Jon Anderson, winner 1973 Boston Marathon, member, 1972 U.S. Olympic team

After my win, Jock ushered me into the Prudential Center to meet the press. When that was over, I asked Jock if I could call my wife and parents. He said, “Sure.” There was a phone nearby, so I picked it up and started dialing. That’s when I noticed Jock looking me straight in the eyes. “Jon, make it collect,” he said. I’m not being critical of Jock. I understand he kept the Boston Marathon alive for many years on a shoestring budget. Apparently, that applied to phone calls.

Bob Hodge, third in 2:12:31 in the 1979 Boston Marathon

When I entered the Boston Marathon in 1974, I personally delivered my application to Jock in the old Boston Garden, where he was known to make toasted-cheese sandwiches on the radiators. I felt the entry was too important to entrust to the U.S. mail. Jock was ubiquitous at New England road races in those days. We all knew him. He was a prickly fellow, but his heart was in the right place. He was unfairly maligned for the K. Switzer debacle, because he was in favor of serious women athletes. He was just trying to enforce the rules as they were at the time.

Tom Derderian, author of Boston Marathon: Year-By-Year Stories of the World’s Premier Running Event

The first time I met Jock, in 1966, I was naked and dripping wet. I was taking a shower after a summer race. He came splashing into the shower, shoes and all, yelling, “Derian? Is there anyone named Derian in here? I’ve got your medal, lad.” He just wanted to make sure a high school kid got his race award. Jock was a complete supporter of the sport and of serious athletes, so long as they followed the existing rules. But he’d go crazy when fraternity guys in clown suits showed up at the Boston Marathon start line wearing number 1.

Patti Catalano Dillon, the first American to break 2:30 in the marathon, and three-time second-place finisher at Boston (1979, 1980, ’81)

I spent about three years running for Jock and the BAA Running Club before I joined Nike. I ran my first two Bostons for the BAA. Jock was a real character. I got to know him well enough to understand his gruffness. He just loved the Boston Marathon so much he wanted to protect it from anyone who didn’t take it seriously. The marathon was like his child, that’s how he felt about it. [Semple and his wife, Betty, never had children.]

When runners like me showed up, he would tell the famous Bruins and Celtics players to leave. He wanted to concentrate on us. He was always kind and generous to me, and I saw him giving plenty of free treatments to others, too. I loved the guy. I was on his massage table the day after every Boston Marathon. He would always say, “Next year, Patti. Next year.”

Gloria G. Ratti, New England road race volunteer since 1971 and current vice president of the BAA board of governors

Jock and I worked together at many races, but his brusque manner invariably put me in a guarded mode, and I seldom engaged in chit chat with him. He respected and appreciated my help, but since my husband, Charlie, ran for the rival North Medford Club, he kept me at a distance.

I remember once I told Jock we should take post-entries at the Mount Washington race and simply charge an extra dollar for them. He grudgingly agreed. Afterwards, he looked very pleased when I gave him the post-entry funds. For several years I worked on weekends in our Hopkinton office, and Jock would occasionally stop by. Again, he was always courteous and appreciative.

Rick Bayko, 17th place, 1974 Boston Marathon in 2:20:57; owner Yankee Runner, Newburyport, Massachusetts

I got to know Jock in 1964 when I started running for the North Medford Club. We were the archrivals of Jock and his BAA runners. The other guys in my club told me Jock was a mean SOB. Then in 1971 when I had an injury, Coach Billy Squires told me to go see Jock at his hole-in-the-wall in the Boston Garden.

I crept into his lair with more than a little trepidation—and found a completely different person. This Jock was smiling and chatty except when the phone rang from some guy asking a stupid question about the Boston Marathon. (This was August, mind you.) Jock would bark at the guy, hang up, grouse about it for a few minutes, and then return to jolly Jock. He saw me daily until I was healed, never charged me a cent, and became a friend even though I ran for the enemy. I’m glad I got to know him the way I did. Jock was great for our sport.

Greg Meyer, winner 1983 Boston Marathon in 2:09:01

Jock was still around when I won Boston in 1983. I remember going to visit him for a massage at the old Boston Garden. He was very much the old school athletic trainer. I loved listening to his stories. He was a good man caught up in a bad moment in the 1967 race.

Phil Ryan, BAA running club member, 1965 to present, finished in 35th place in 2:29:31 in the 1971 Boston Marathon

The Kathrine Switzer photo does not show what a super-nice person Jock was. He was a friend not just to BAA runners like me, but to all runners. He was a great motivator to me. There was nothing like seeing his smile after we had a good BAA team race. You have to remember that Jock didn’t make up the rules that said women couldn’t run distance races. That was the International Olympic Committee. Jock was just enforcing the rules.

Tom Fleming ran 2:37:36 for 68th place in the 1970 Boston Marathon but improved to 2:12:06 for third in 1975

I met Jock in April 1970, as I was lining up right behind the Boston Marathon studs like Ron Hill, Jerome Drayton, Eamon O’Reilly, and Kenny Moore. Jock asked me what I was doing up there and said, “Don’t you dare touch them.” But then he gave me a cheerful, “Okay, kid, learn your lessons well today.”

As I got to know Jock better in the roaring 1970s of American road racing, he became one of my biggest fans. Of course, a Semple would have to love a Fleming. We shared the Scottish thing. I only saw him once a year, at Boston, but he was always encouraging. He was a loud teddy bear, really. By the way, I love those photos of him chasing Kathrine in 1967. He made a worthy effort, but history was passing him by on that day.

Proceeds from sales of the newly released book Just Call Me Jock go to the Barb’s Beer Foundation, which is racing to find a cure for lung cancer.