The mystique of a writer’s notebook seems still to be with us in this digital age. Perhaps it’s because a handwritten original is unhackable – other than by traditional means, such as burglary. But it’s no doubt a matter too of the way notebooks seem to offer access to hidden origins, and to the creative processes by which works we value come into being. Notebooks record early versions and impulses, and though sometimes the writer has an eye to posterity, the privacy of self-communing allows things that can’t be shared with others to be said, within what Coleridge, one of the great notebook-keepers, called in 1808 a “Dear Book! Sole Confidant of a breaking Heart”. For Virginia Woolf, her notebook helped to “discover real things beneath the show”; flashes of perception, phrases, half-formed and potential ideas – and of course stray bare thoughts (see Kafka: “Never again psychology!”; or Mark Twain: “Wife perfect but blamed if she suits me!”).

Jotting things down in a notebook is one way writers shape and discipline the unpredictable flow of ideas. For Henry James, in 1881, just after publishing The Portrait of a Lady, it was already a matter of regret that he had “lost too much by losing, or rather by not having acquired, the note-taking habit”. But he would make up for it over the next 30 years by filling innumerable pages with his records of story ideas, anecdotes from dinner parties and newspapers, things noticed on his travels. He developed personal rituals around the process of expressing his thoughts, through the pressure of pen on paper.

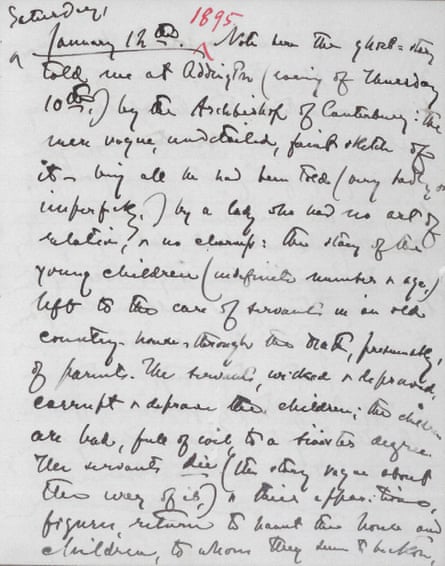

Increasingly he saw the notebook as the answer to … well, everything: “the only balm and the only refuge, the real solution of the pressing question of life, are in this frequent, fruitful, intimate battle with the particular idea, with the subject, the possibility, the place.” James burned many of his notebooks, but for some years I’ve been re‑editing those which survived for a new scholarly edition (still in progress, for Cambridge University Press). They’re classics of the form, full of wonderful writing and thrilling passages – such as the account of the evening when the Archbishop of Canterbury told James the vague ghostly anecdote that became The Turn of the Screw. They also contain about 60 subjects that he never got round to writing.

“I hate to touch things only to leave them,” James wrote; which gave me the idea of trying to find contemporary writers who might find the orphaned subjects inspiring and bring them to life. These new works stand in their own right as the authors’ creations. Here three of those writers muse on their own uses of notebooks and the Jamesian ideas that inspired them. Philip Horne

‘Note-taking is a way to tell yourself a story, it becomes a mode of being’ – Paul Theroux

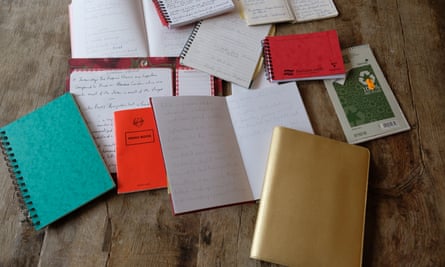

Note-taking is not just a method for remembering. It is a way a writer tells himself, or herself, a story – and this becomes a process of life, a mode of being. Writers are constantly talking to themselves. When the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, sent a sizeable truck to my storage unit two years ago to pick up my archive, they were able to fill the body of the truck with boxes of my papers. About a third of this haul were notebooks – travel notebooks, notebooks containing first drafts of novels, big ones, small ones, thickened with inky pages, some with sketches and doodles, many with complete stories.

I have been a note-taker all my writing life, which is almost 60 years. Life moves at such a pace that note-taking is a necessity. A travel book is not possible without a daily account of what’s happened. The writing of a travel book depends on the notes taken en route – dialogue, description, insights. Travelling alone, I usually write my notes at mealtimes – at dinner or breakfast, catching up, always in ink.

But when I surrendered my papers to the Huntington I kept some boxes back. These contained a good number of pocket-sized notebooks, filled with ideas for stories, fragments of dialogue, possible names. For many years I accumulated notes for a story about a well-intentioned American, who returns to the African village where he’d been a teacher. My idea was that he would bring money and hope; that the village would welcome him and then not let him leave; and when his money was gone, he would be sold. After a long time, playing with this idea, I finally wrote my novel, The Lower River, using these years of notes.

I was not surprised by the number of notebooks in which Henry James recorded his ideas for stories – he had an intensely active mind, a vivid imagination and, being social – a constant diner-out – he was the recipient of all sorts of snippets, gossip and asides. And he was lonely, another trait of the note-taker. It is not a surprise that he did not get around to using all this material. Some writers struggle to come up with a new idea. Others keep notebooks.

‘My notebooks are a jumble of poetry, prose and daunting instructions’ – Susie Boyt

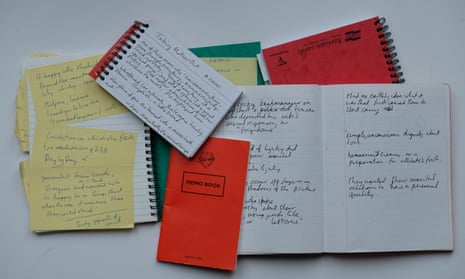

I have always kept notebooks – messy little attics of the mind, an odd assortment of shapes and colours stuffed into drawers next to defunct phones and balls of string. They feel private and tender, a bit like night clothes; or embarrassing, like over-eager little sisters.

I admire writers who operate their notebooks rigorously, with mathematical co-ordinates of character and plot, in the fashion of the Euston Road School painters, but mine are filled with a jumble of poetry, prose and criticism, lists, plans, with occasional personal anecdotes in which I often emerge the slightee.

(Gave Dad Young Törless by Robert Musil. Dad: “It’s SO adolescent.”)

I found 11 dating from 2003 until the present and leafed through them trying, for appearances’ sake, to seem aloof. There are daunting instructions: write a novel with two heroines, structured like a three-act play (a suggestion I obeyed in my last novel Love & Fame). There are phrases which have impressed me, sometimes unattributed. Unfamiliar stereotypes. Rain like ruled lines. Betjeman’s love of the “beefy enchantress” (“She seemed such a contented woman, dividing her enthusiasm between puddings and literary work”). Elizabeth Taylor.

The poetry is largely American: “Too often when you thought you’d be showered with confetti / What they flung at you was a plate of hot spaghetti” – John Ashbery. Weldon Kees: “The tambourine did not function with its usual zest’’. WK: “The sky like faded overalls”; “vein-violet”.

Sometimes there are found items. Notice in St John’s Wood Library: “Temporary housekeeper wanted for two weeks. (Wife going away.) Live in. Luxury apartment.” (That inspired a chapter of my fourth book Only Human.)

There are wistful musings: did Cole Porter really understand about love?

There are daring suggestions: have sausages frying throughout the scene.

Occasionally there’s a to do list: green paint samples; nutritionist; kitchen floor; sort out Liza Minnelli – that could mean so many things …

I audition lines of dialogue sometimes: “Nothing’s happened honestly. I just swanned about a bit in my pants.”

For 25 years I have attended Henry James reading groups so his voice often appears, almost casually, like a distinguished neighbour dropping round.

HJ says Paris is “Brighton but at a hundredfold”.

HJ on St Peter’s in Rome: “Even for the profane ‘constitutional’ it serves where the Boulevards, where Piccadilly and Broadway, fall short.”

Looking at James’s notebooks recently I was pleased to see he sometimes wrote encouraging messages to himself.

I didn’t know that was allowed.

‘I leave the first pages untouched, in case I begin to write a novel’ – Amit Chaudhuri

I was taking a year off from university in England in 1986, and spending time with my parents in St Cyril Road in Bandra, which was then still on the outskirts of Bombay.

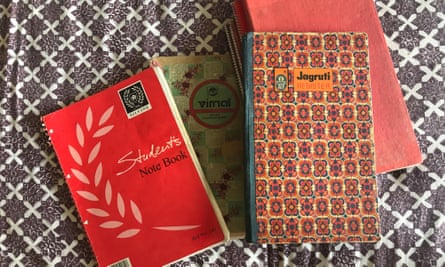

I walked to buy a notebook from a provisions store – I was thinking of beginning what would be my first novel, A Strange and Sublime Address. I made do with what they had: a hardcover exercise book with clothbound spine, the words “Jagruti Register” on the front. It was meant for keeping accounts, though jagruti, or “awakening”, sounds significant in retrospect. I began my novel – about a boy from Bombay visiting his uncle’s house in Calcutta – seemingly without hesitation or preliminary notes, though I would scribble lines and make points in the blank space at the top of the page. For instance, above the unequivocal “One” (the heading of a chapter I discarded), there is, written in a microscopic hand, a line I neither used nor developed: “The days exploding like little crackers”.

Instead of plot, I had a surfeit of excitement, to do with some inkling of the momentous. This surfeit meant that a lot of what’s in that book is unused. At the back, I find terse briefings for things I did write of: “1) Jhadu – collection of filth, hair, feathers 2) Babla cries, insect in ear”, and, floating near these, “Chhotomama’s backache ‘A little to the left’.” The first refers to a description I wanted to slip in, of the rubbish that a maidservant’s jhadu or broom accumulates while sweeping. The second is a reminder to include an episode in which an insect trespasses into the ear of one of the boy’s cousins. The third has to do with the boy’s uncle commanding a son to press his back. Odds and ends are what I was collecting.

In keeping with this project, I find a credo inscribed untidily on the second last page: “Reality is as multifarious, if not more, than the imagination.” For my second novel, Afternoon Raag, I bought an exercise book with the name “Vimal Accounts Register”. I was intent on writing a short novel by assembling an array of instants. So the notes at the back resemble a laundry list of non-happenings. Most of these I wouldn’t follow up on; superstitiously, I stopped writing down points, and the last pages simply contained lines as yet without a context, waiting to enter the main text.

By my third novel, I began to write in red A4 Silvine notebooks bought from the Tuck Shop in Oxford, and I continue to do so. These seem to be only available at that particular shop. I leave the first pages untouched, in case I begin to write a novel; at the back, I jot down poems, essays and thoughts. So these Silvine notebooks, when I consult them, must be opened from the back, like an Arabic text.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion