Cop26 starts on 31 October and is scheduled to close at 6pm on Friday 12 November, but is likely to run on into the Saturday or perhaps later still, as previous climate conferences have done. World leaders will attend the opening days and after they depart the crunch negotiations will be done by their representatives, environment ministers or other high-ranking officials.

Alok Sharma

As host, the UK will take the pivotal role at the talks, with the cabinet minister Alok Sharma designated Cop president. His job will be to corral 196 nations into agreeing national plans on greenhouse gas emissions that add up to a global plan for limiting temperature rises to 1.5C. Since his appointment in February 2020, this former international development secretary with an understated manner but relentless application has impressed governments and campaigners alike with his diligence, commitment and integrity.

Boris Johnson

The UK prime minister was a late convert to climate action, having scoffed at climate science in his Telegraph column as recently as 2015. Observers have been exasperated by his perceived failures: the absence of a clear net zero strategy in the UK, few public appearances highlighting climate until recently, when he raised groans at the UN for riffing on Kermit the Frog, and a lack of “grip”. Yet his volatile mixture of charm, optimism, camaraderie and cunning – and his undoubted capacity to surprise – could yet prove a winning combination.

Nigel Topping

Only national governments have negotiating powers at Cops, but sub-national governments – at state and city level – also hold power over emissions. So do businesses and other institutions, and a key aim of this Cop is getting a wide range of “non-state actors” to sign up to net zero emissions targets for 2050, with emissions cuts this decade to align with that goal. Called the Race to Zero, this initiative is co-led by Topping, a high-level champion for climate action.

Mark Carney

The former governor of the Bank of England is a climate envoy twice over, appointed by the UK and the UN. His role has involved gathering banks into the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero to reassess and reform their investment portfolios, tilt them towards low-carbon technologies and services and cut their fossil fuel investments. More controversially, he has become a figurehead for carbon offsetting.

António Guterres

“Humanity is waging war on nature. This is suicidal. Nature always strikes back – and it is already doing so with growing force and fury.” The UN secretary general’s forceful warning last year was followed up with a further warning this summer that we are facing “code red for humanity”, after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change gave its starkest warning yet on global heating. Guterres has made the climate crisis central to his mission, with the Covid crisis providing further impetus as an example of how badly things can go wrong when countries fails to heed scientific warnings.

Patricia Espinosa

As the executive secretary of the UN framework convention on climate change, the parent treaty to the 2015 Paris accord, Espinosa is the UN’s most important climate official, and one of only a handful of women at the top table in these talks. A former foreign secretary of Mexico under Felipe Calderón’s presidency, she has been less outspoken than her predecessor in the UN role, Christiana Figueres, preferring to take a backroom approach to the negotiations.

Mario Draghi

The UK is co-hosting the Cop26 talks with Italy, though the Cop itself will take place in Glasgow, and the launch of the Italian co-presidency in February 2020 was quickly overshadowed by Covid-19. Draghi took over as prime minister from Giuseppe Conti, who attended last year’s launch. Italy’s hosting duties have included a youth Cop and a pre-Cop meeting of ministers. It also holds the revolving presidency of the G20, whose leaders will meet in Milan days before the Glasgow summit begins. The meeting will be keenly watched for signs of movement.

Roberto Cingolani

A physicist, Cingolani brings scientific heft to his role as Italy’s environment minister, having been director at the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia in Genoa from 2005 to 2019, and previously worked at Germany’s prestigious Max Planck Institute. He hosted the pre-Cop in Milan.

Joe Biden

Taking the US back into the Paris climate agreement was one of Biden’s first acts as president, and he has made climate a core part of his presidency. The US is the world’s biggest economy and second biggest emitter, and its role has always been pivotal at the talks, along with that of China, the biggest emitter and second biggest economy. But tensions with China over trade and national security have cast a shadow over the US’s climate diplomacy. Before the Paris summit in 2015, Barack Obama held a key summit with Xi Jinping of China as a stepping stone to the accord. Biden is said to have had a constructive phone call with Xi, but there is speculation as to whether it will be enough.

John Kerry

As secretary of state, Kerry signed the Paris climate agreement for the US, with his granddaughter on his lap. The former US senator and presidential candidate is now Biden’s special envoy on climate, and has spent much of the year visiting foreign capitals in a strenuous round of diplomacy aimed at forging a broad coalition to implement the agreement. He chose Kew Gardens in London for a major intervention on the climate this summer, appealing to China to step up with stiffer emissions cuts.

Ursula von der Leyen

The EU negotiates as a bloc at the UN talks, and sees itself as the global leader on climate action, having embedded strong climate policies over two decades, such as renewable energy and emissions targets. During the presidency of George W Bush in the US, the EU almost single-handedly kept the flame of international climate action alive, and it played a pivotal role in more recent Cops. If the UK is astute, the EU could be a useful ally in talking to China – which is needed, given the repercussions of the Aukus deal and continuing differences over trade. But will Johnson be willing to make such overtures?

Frans Timmermans

The former Dutch foreign minister, a leftwing MP for many years and the EU’s executive vice-president, has vast experience and cuts an impressive figure at the talks. Timmermans has a reputation for straight talking but is skilled at the sort of late-night horse-trading that often accompanies Cops, though his responsibilities for seeing the EU green deal through a fractious legislative process have occupied much of his time in the past year. He takes the climate crisis personally, and has warned that today’s children face wars over food and water if countries do not succeed in cutting emissions.

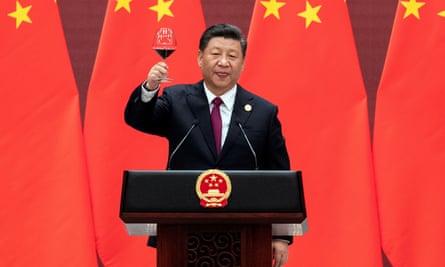

Xi Jinping

Xi helped the prospects for Cop26 last year at the UN general assembly when he committed China to reach net zero emissions by 2060 and to peak emissions by 2030. While vital progress, that is not enough to keep the world to 1.5C, and many are hoping China’s emissions will peak by 2025. Xi will not attend Cop26 but senior figures say his absence does not spell disaster for the talks – he is capable of instructing his negotiating team to make the progress needed.

Xie Zhenhua

The veteran Chinese climate envoy has been a key figure at Cops for more than a decade, and his reappointment to the role this year was seen as a positive sign of China’s intention on closer engagement at Cop26. Genial, sometimes outspoken and widely respected, he has held talks with Kerry and, separately, Sharma, describing the talks with Sharma as “candid, in-depth and constructive”.

Narendra Modi

Will India embrace a net zero emissions target? The Guardian understands that the Indian prime minister was on the verge of doing so this spring, only for the worsening Covid pandemic to stay his hand. For the coal-dependent nation such a step would be significant – and aligned with the economic forces already at work in India, where new solar and wind power are far cheaper than new coal-fired plants. However, India has long said all substantial emissions-cutting efforts must come from developed countries, which bear historical responsibility – even though recent figures show its cumulative emissions since 1850 outstrip those of the UK.

Jair Bolsonaro

At Biden’s climate summit earlier this year, Brazil’s president promised to double the budget for protecting the Amazon, only to renege within days. The destruction of the Amazon that he has overseen – and many would say encouraged, though his administration denies this – have brought the world’s biggest rainforest, a huge carbon sink, to the brink of becoming a source of carbon. Brazil helped to wreck the last Cop, in 2019, over the technicalities of carbon trading. The subject is up for discussion again at Cop26, but the question is whether this time the UK hosts are able to outflank Brazil.

Scott Morrison

“A rogue nation on the climate” is how one Cop expert describes Australia, urging other countries to ostracise the coal exporter, which under Morrison has refused to take on new commitments on emissions. But if anything the Aukus deal appears to have buoyed the Australian prime minister’s sense that he can get away with it – he may not even attend.

Non-politicians

The Queen

The UK’s secret weapon? The Queen has confirmed she will be attending Cop26, and will welcome leaders to the summit. The world’s longest-reigning monarch commands global attention and respect, even among republics and republicans.

Prince Charles

Charles made his first public speech on the environment in 1970 and has been a staunch advocate of conservation and other environmental causes since, assembling groups of businesses to commit to emissions targets. In January he launched Terra Carta, asking organisations to sign up to environmental principles, and this summer hosted Kerry at Clarence House. He has attended previous Cops, but in a low-key fashion as protocol dictates.

Sir David Attenborough

The veteran naturalist has spent recent years highlighting environmental issues such as plastic in the ocean, species loss and the climate crisis. Generations of children around the world have grown up on his nature documentaries, making him a key spokesperson for planetary safety.

The pope

Pope Francis has made the climate a touchstone for his papacy, starting before Paris with the Laudato Si encyclical that enjoined Catholics to “care for our common home”.

Greta Thunberg

The youth activist, whose school strikes sparked a global youth protest movement, recently told the Guardian: “[At Cop26] the leaders will say we’ll do this and we’ll do this, and we will put our forces together and achieve this, and then they will do nothing. Maybe some symbolic things and creative accounting and things that don’t really have a big impact. We can have as many Cops as we want, but nothing real will come out of it.”