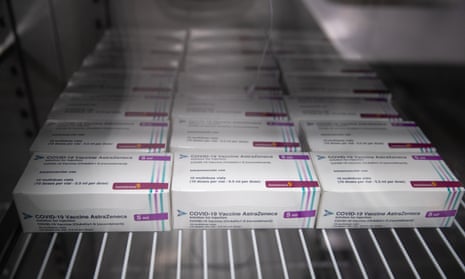

The government’s contradictory approach to the global distribution of coronavirus vaccines risks undermining the impressive contribution that UK science has made to tackling the pandemic. Although the UK is the most generous funder of Covax, and the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine will be made available at cost in the global south, we have joined other wealthy countries in hoarding large amounts of vaccines. This limits the supply to more vulnerable people in low-income countries and is morally wrong and strategically shortsighted. The pandemic must be tackled everywhere for UK citizens to be truly safe, and becoming “global Britain” requires us to ensure that the fruits of our scientific prowess serve for the benefit of all. This is a case in which ethical demands coincide with our national interest.

We urge the government to take three steps: first, to generously finance vaccine distribution in low-income countries and support distribution in ways that strengthen health systems for the long term; second, to promote the expansion of production capabilities in the global south, so that more firms can produce vaccines; and third, to distribute a significant proportion of our supply to low-income countries.

While the UK has been impacted hard by the pandemic, we remain a world leader in global health and development research. This needs to be aligned to a vision and form of political leadership that prioritises a more cooperative approach to global vaccine supply and delivery.

Prof Sam Hickey President, Development Studies Association; Global Development Institute, University of Manchester

Prof Melissa Leach Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex

Prof Diego Sánchez-Ancochea Oxford Department of International Development, University of Oxford

Prof Uma Kambhampati Secretary, Development Studies Association; Department of Economics, University of Reading

Prof Kathryn Hochstetler Department of International Development, London School of Economics

Prof Michael Walls Bartlett Development Planning Unit, University College London

Prof Zoë Marriage Department of Development Studies, Soas University of London

Dr Elisa Van Waeyenberge and Dr Hannah Bargawi Economics department, Soas University of London

Dr Jonathan Fisher International Development Department, University of Birmingham

Prof PB Anand Peace studies and international development, University of Bradford

Prof Jean Grugel Interdisciplinary Global Development Centre, University of York

Prof Philip N Dearden Centre for International Development and Training, University of Wolverhampton

Prof Laura Camfield School of International Development, University of East Anglia

Prof Alfredo Saad-Filho Department of International Development, King’s College London

Dr Grace Carswell Head of international development, University of Sussex

Prof Khalid Nadvi Head of the Global Development Institute, University of Manchester

Dr Shailaja Fennel Centre for Development Studies, University of Cambridge

Prof Frances Stewart Professor emeritus of development economics, University of Oxford, and ex-president, Development Studies Association

The argument about vaccination strategy between the doctors of the British Medical Association and the scientists on the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation may have more to do with ethics than the underlying science (Doctors call for shorter gap between Pfizer Covid vaccine doses in UK, 23 January; UK vaccine adviser says delay of Covid second dose will save lives, 24 January).

The BMA has a Kantian (rule-based) moral philosophy typified by the Hippocratic oath. Doctors have an obligation to do the best they can for each patient, and any action or inaction that causes potential harm to a patient is deemed to break this obligation.

On the other hand, scientists on the JCVI take a utilitarian view of moral philosophy, seeking the greatest good for the greatest number. They argue that lives are likely to be saved by delaying the second dose to individuals, even if some of those individuals become vulnerable again.

Perhaps the two parties should stop arguing that they have the right interpretation of the science and recognise a fundamental and honourable philosophical disagreement. It is the function of the government to decide which moral stance to support.

Prof Paul Glendinning

Marsden, West Yorkshire