Catholic and Protestant leaders have stressed their mutual bonds 500 years after the start of the Reformation, a movement that tore apart western Christianity and sparked a string of bloody religious wars in Europe lasting more than a century.

A service in Westminster Abbey on Tuesday marked the anniversary of the date in 1517 on which the German theologian Martin Luther submitted The 95 Theses to the archbishop of Mainz, as well as nailing a copy to the door of a church in Wittenberg, lighting the fuse of the Reformation.

The archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, presented a text by the Anglican communion affirming a joint declaration by the Roman Catholic church and global Protestant bodies, described as “a sign of healing after 500 years of division”.

In his address, Welby said the text acknowledged the religious, political and social changes triggered by Luther, but also the Reformation’s “dark side”, including individualism, division, cruelty and war.

“For each of the things that came through the Reformation – good as they are, precious beyond compare, even – for each there is also a dark side,” he said. “With new vigour came conflict. With individual understanding of grace came individualism and division ... With literacy and freedom came new ways of cruelty refined by science. With missionaries bearing the faith came soldiers bearing the flag.”

John Hall, the dean of Westminster, told the congregation: “We recall, with sadness, the cruelty and deaths that blighted the ensuing decades and, with gratitude, the determination and trust that endured to the end and conquered through suffering.”

Prayers were said by representatives of Protestant churches and by Cardinal Vincent Nichols, the archbishop of Westminster and leader of the Catholic church in England and Wales.

In Wittenberg, the German chancellor Angela Merkel and president Frank-Walter Steinmeier took part in a service in the Castle church, where Luther supposedly posted The 95 Theses. The city also celebrated the anniversary with a medieval-style street festival, which included arts and cultural events.

Last week, Pope Francis said Catholics and Protestants were now enjoying a relationship of “true fraternity” based on mutual understanding, trust and cooperation.

He told Derek Browning, moderator of the Church of Scotland, who was visiting the Vatican as part of the Reformation commemorations, that the two traditions were “no longer … adversaries, after long centuries of estrangement and conflict”.

The pontiff added: “For so long we regarded one another from afar, all too humanly, harbouring suspicion, dwelling on differences and errors, and with hearts intent on recrimination for past wrongs.”

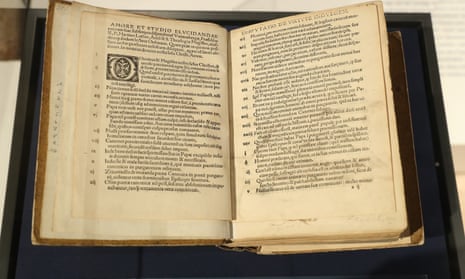

The 95 Theses, written in Latin, was a backlash against increasing corruption in the Catholic church and, in particular, the highly profitable sale of “indulgences”. These promised a fast-track to heaven and were sold to fund the building of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Luther argued that salvation could not be bought or brokered by the church, but was a matter between an individual and God.

His challenge to the authority and elitism of the Catholic church was translated into German and other European languages. Thanks to revolutionary new printing presses, his message spread rapidly and was taken up by others, including the French theologian John Calvin.

Rome condemned Luther as a heretic and launched the Counter-Reformation, but by the end of the 16th century most of northern Europe was Protestant.

In England, Henry VIII, desperate to dissolve his marriage to Catherine of Aragon in pursuit of a male heir, launched his own, less clear-cut, separation from the Catholic church which involved the destruction of much of the country’s religious heritage.

In 1999, the Catholic and Lutheran churches agreed a “joint declaration on the doctrine of justification” that resolved many of the theological issues at the heart of the schism. This document has now been welcomed and affirmed by the Anglican communion.

A spokesperson for the Catholic church in England and Wales said: “The desire for reconciliation is such that mistakes can be recognised, injuries can be forgiven and wounds healed.

“We give thanks to the joy of the gospel we share as Christians, express repentance for the sadness of our divisions and renew our commitment to common witness and service to the world.”

But despite the warm words of reconciliation issued by leaders, there are issues blocking the prospect of a reunification of the two traditions, not least that of female priests.

Meanwhile, pockets of sectarianism remain in parts of northern Europe, including Northern Ireland and Scotland.

Last year, a document released by an evangelical Protestant group, Reformanda Initiative, drew a distinction between individual Catholics and the “unchecked dogmatic claims and complex political and diplomatic structure … [of the] institutional Catholic church”.

It concluded: “The issues that gave birth to the Reformation 500 years ago are still very much alive in the 21st century for the whole church.”